How to treat a fistula

The concept of fistula implies an open channel between any organ and the surface of the body, otherwise it is also called a fistula.

As a rule, a fistula forms as a result of a complication after surgery or an advanced disease. Fistula can only be treated surgically; only granular fistulas can heal on their own. What types of fistulas are there:

Rectal, rectovaginal, duodenal, bronchial, gastric. Based on its shape, the fistula can be complete or incomplete.

What are the causes of fistula

- tuberculosis, Crohn's disease;

- actinomycosis;

- tumors;

- paraproctitis;

- surgical intervention;

- diseases of ENT organs;

- Dental complications.

Rectal fistulas

Home» Diseases» Rectal fistulas

Make an appointment with a proctologist in St. Petersburg

How to prepare for a consultation with a proctologist

Since Henry Ford made his very controversial gift to humanity in 1913 by launching the first assembly line, and the genius of “The Great Dumb” Charlie Chaplin showed us all the “charm” of this type of labor organization, assembly line production has captured more and more new areas of working life. . This cup has not passed from medicine, so the times of Professor Preobrazhensky, who with one hand transplanted the pituitary gland of the King of Nature to an unfortunate dog, with the other hand sewed on the ovaries of his closest primate relative, while not forgetting to think about which act of “Aida” to catch up with this evening, modern doctors (at least in my person for sure) are perceived with great envy. The so-called “information explosion” has led to the fact that the volume of information in the world increases annually by 30%, and over the past five years, humanity has produced more information than in the entire previous history, so in the 21st century, read five treatises on medicine, albeit thick ones and tedious, but still not endless, and becoming a Doctor from the ancient legends about Hippocrates and Avicenna, unfortunately, is already absolutely unrealistic.

Medicine is becoming more and more fragmented, and when you specialize in one area or another, you begin to gradually lose the knowledge accumulated at the institute as unnecessary. This is a very slow process, but absolutely inevitable. You begin to practice surgery, and gradually all your knowledge of therapy is covered with a light foggy haze, which is well illustrated by a bearded medical joke: “What is a blind research method? Surgeon assessing electrocardiogram. — What is a double-blind research method? Two surgeons assessing the ECG." Then you become a coloproctologist, and after some time you try to remember when was the last time you had, for example, an appendectomy, and suddenly you realize that it was 8-9 years ago

As a result, specialization and long work in a planned surgical department lead you to classic assembly line production, when day after day you “get to the machine” and perform at most a dozen variations of absolutely standard operations. The advantages of the conveyor belt in relation to surgery are obvious - after some time, you begin to do these dozen operations really well (and this is not at all because you are a surgical genius - even circus bears learn to ride a bicycle in a comparable time with enough training ). But the disadvantages are also understandable - there is very little creativity in this process, so by the time you reach your “40s” you, on the one hand, acquire regalia and “respect”, and on the other hand, you feel that you are becoming stupid, dumb, brutal and finally turning into a craftsman . This is probably part of the problem called the “midlife crisis.”

The advantages of the conveyor belt in relation to surgery are obvious - after some time, you begin to do these dozen operations really well (and this is not at all because you are a surgical genius - even circus bears learn to ride a bicycle in a comparable time with enough training ). But the disadvantages are also understandable - there is very little creativity in this process, so by the time you reach your “40s” you, on the one hand, acquire regalia and “respect”, and on the other hand, you feel that you are becoming stupid, dumb, brutal and finally turning into a craftsman . This is probably part of the problem called the “midlife crisis.”

Why and why did I make this yet another lyrical digression in another article? First of all, of course, I take the chance to do at least something creative, to relieve my soul and diversify a little boring monologues about proctological ailments (and I apologize for wasting time from readers who just wanted to find out specific information on a specific topic), but to fistulas rectum, this introduction is most directly related: in “minor” proctology, the treatment of chronic paraproctitis is the most creative, interesting and unresolved task that brings at least some variety to the gray conveyor belt everyday life.

The doctor’s words “a very interesting disease” should alert any potential patient: medicine is a cruel science, and what is of interest to a specialist is usually associated with a lot of problems for the patient himself. This is exactly the case with rectal fistulas, and this concerns all aspects of the problem: diagnosis, when none of the existing methods (TRUS, fistulography, MRI) satisfies surgeons 100%; preparation for surgical treatment, which requires a considerable amount of time for washing the fistula, fiddling with drainage ligatures, etc. and so on.; surgical treatment itself, characterized by a wide variety of surgical procedures, a high risk of complications (primarily incontinence of intestinal contents) and often not the most impressive treatment results even in specialized proctology centers.

Information about general approaches to surgical treatment of rectal fistulas, indications for one or another surgical procedure, expected treatment results and possible complications can be found in the article “Treatment of rectal fistulas.” Below is general information about the disease: definition, classification, diagnostic methods.

What is a rectal fistula?

According to domestic clinical guidelines, three definitions are equally applicable for this disease: chronic paraproctitis, anal fistula, rectal fistula , and in the English-language literature the term anal fistula .

Rectal fistula is a chronic inflammatory process in the anal crypt, intersphincteric space and pararectal tissue, accompanied by the formation of a fistula tract.

As always in medicine, it seems to be a comprehensive and simple definition, but it is so overloaded with specific anatomical and medical terms that without another brief excursion into anatomy, mastering further information will be very difficult.

The first point related to anatomy is what are anal crypts? The dentate line (2 in the photo above) is the upper border of the anatomical anal canal, up to it it is lined with stratified squamous non-keratinizing epithelium (anoderma), above there is a short (5-7 mm) zone of transitional epithelium (“transformation zone”), which then passes into the single-layer columnar epithelium of the rectum. The rectal mucosa above the dentate line forms vertical folds (from 5 to 14, more often 6-8), the so-called morgani columns (4 in the photo above), which below, forming the dentate line, are connected by semilunar morgani valves, forming small depressions - blinking crypts , into which the ducts of the anal glands open, secreting a secret that moisturizes the anal canal and facilitates defecation, like in all mammals on our planet. It is believed that it is the anal crypts and their ducts that are the gates of infection during the development of acute and chronic paraproctitis, therefore the main theory of the development (pathogenesis) of the disease today is called cryptogenic.

The second point related to anatomy is what is pararectal tissue and intersphincteric space? The anal canal and rectum are surrounded by cavities filled with loose fatty tissue, which is an excellent nutrient substrate for bacteria. Therefore, very often inflammation that begins in the anal crypts moves into these cavities with the formation of purulent abscesses of varying degrees of size, depth and, accordingly, the complexity of surgical treatment (the so-called acute paraproctitis). As can be seen in the figure, borrowed from a Soviet monograph on the treatment of paraproctitis, there are subcutaneous, limited by the skin and subcutaneous fascia, ischiorectal, limited by the fascia and the muscular-connective tissue diaphragm of the pelvis, and pelviorectal, limited by the pelvic diaphragm and peritoneum, cellular spaces. It is clear that the deeper the abscess is located, the more difficult the diagnosis, the surgical technique and the more serious the complications, up to the transition of the purulent process into the abdominal cavity. Separately, there is a narrow intersphincteric space located between the fibers of the internal and external sphincter of the anus, which is involved in the purulent process in the vast majority of cases, due to the anatomical features of the location of the anal glands themselves.

For those who want to get a closer look at the anatomy of this zone, I recommend reading the article “Anatomy and Physiology” on our website.

Summarizing the knowledge gained, a rectal fistula has three mandatory components: a hole in the intestine at the level of the affected crypt (internal opening of the fistula), a purulent cavity or several cavities remaining in the tissue surrounding the intestine and anal canal after the acute inflammatory process subsides, and the fistula tract itself, connecting them. In the vast majority of cases, there is also an opening in the skin (external fistula opening) and another part of the fistulous tract from the external opening into the purulent cavity.

What causes rectal fistulas to form?

In medical language, this section is usually called the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease, but translated into universal human language, its meaning is precisely this - why, in fact, do rectal fistulas occur? For the most part, the answer to this question has already been stated in the previous section: in 95% of cases, the formation of a rectal fistula is preceded by acute purulent inflammation in the crypt and perirectal tissue, called acute paraproctitis (our website has a separate article about this disease). At the same time, after an acute process, a fistula does not always form: according to medical statistics, this occurs in approximately 30-50% of cases, and the main factors contributing to the transition to the chronic phase are the complexity of the disease itself (depth, size of the abscess, etc.) and inadequate surgical tactics.

Other relatively rare causes of fistula formation are:

- Iatrogenesis (more on this term below)

- specific infectious agents (actinomycosis, tuberculosis)

- inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease)

Behind the beautiful term “iatrogenics” medicine hides its own mistakes, i.e. Iatrogenic diseases are diseases that were caused by previous vigorous medical activity. In relation to the topic under discussion, the main “suppliers” of patients with iatrogenic fistulas are proctologists and obstetricians-gynecologists themselves. Acute paraproctitis is a standard complication of all types of operations on the rectum and anal canal, including the “simple” ones, such as hemorrhoidectomy and excision of anal fissure. There are no simple operations in surgery at all (which is why I put this word in quotes), so here you can immediately give standard advice - it is better to have surgery in specialized clinics, where the percentage of such complications does not exceed 1%. The “sloppy” work of obstetricians and gynecologists leads to the formation of two types of fistulas - rectal fistulas themselves, opening either into the vestibule of the vagina or into the suture after an episiotomy, and rectovaginal fistulas, i.e. fistula tracts between the intestine and vagina (the latter are a topic for a separate discussion).

I have never encountered fistulas associated with tuberculosis in my practice, so I find it difficult to say anything new and wise about this beyond what is written in the classical manuals on proctology, except that this is apparently a very, very rare problem. But actinomycosis of the perineum is a pathology that we encounter from time to time, albeit infrequently, approximately once every 2-3 years. There are many disadvantages of living in a large metropolis, but there are also a lot of advantages, and one of them is that in St. Petersburg there is a specialized institution that deals with mycoses - the Research Institute of Mycoses, with which we actively cooperate in the treatment of this difficult category of patients.

Acute and chronic paraproctitis, which is a consequence of Crohn's disease, is a common problem, but also very specific. Both in the case of actinomycosis of the perineum and in the case of Crohn's disease, the pathological process is characterized by the formation of multiple purulent foci in the perineal area and fistulous tracts connecting them, which requires first of all treatment of the underlying disease; the surgeon is involved in the treatment step by step and only for the sanitation and drainage of large purulent cavities. Due to the mass of features, it is more logical to discuss both problems in separate articles, which, we hope, will get around to it someday, at least there are such plans. Further we will talk only about classical cryptogenic and iatrogenic rectal fistulas.

What are rectal fistulas (classification)?

The full classification of chronic paraproctitis, adopted in our country and set out in domestic clinical recommendations, is given below:

By type of fistula

- full

- incomplete (internal)

By localization of the internal hole

- rear

- front

- side

According to the location of the fistula tract:

- intrasphincteric

- transsphincteric

- extarsphincteric

Separately, high rectal fistulas (high-level fistulas) are distinguished, in which the internal opening is located not in the crypt area, but in the lower ampullary section of the rectum, which in the vast majority of cases is associated precisely with the iatrogenic nature of the disease. There are also additionally 4 degrees of complexity of extrasphincteric fistulas :

1st degree: the internal opening is narrow, without scars, with a straight course, without abscesses and infiltrates in the surrounding tissue

2nd degree: scars in the area of the internal opening, without inflammatory changes in the tissue

3rd degree: the internal opening is narrow, without scars, but with a purulent-inflammatory process in the tissue

4th degree: the internal opening is wide, scarred, with a purulent-inflammatory process in the tissue

We touched on the issue of complete and incomplete fistulas at the beginning of the article: an incomplete fistula has only one fistula opening in the intestine, a complete one has two, internal in the intestine and external on the skin of the perineum. Incomplete fistulas are rare, in most cases they are a complication of a long-standing chronic anal fissure, or a previous proctological operation, and are rarely complex. This issue has minimal impact on the choice of treatment option, and is interesting only because of the possible difficulties in diagnosis: an incomplete fistula is more difficult to detect.

Localization of the internal opening is an issue that significantly influences treatment tactics. Internal fistula opening on the side walls is rare, which is due to the anatomy of the rectum (there are fewer anal glands on the sides). The posterior fistula opening is the most common and, again, due to the anatomy of the rectal muscle sphincter, presents less difficulty for the surgeon. Anterior fistulas are problematic in women, especially those who have given birth, since the muscle sphincter along the anterior wall of the intestine is thinned, and surgical manipulations in this area carry a very high risk of resulting in incontinence of intestinal contents. In many foreign manuals, this type of fistula is classified separately, and in any case, doctors with sufficient experience in the surgical treatment of chronic paraproctitis should treat them.

Finally, the main classification that determines further surgical tactics is the relationship of the fistula tract to the muscle fibers of the external and internal sphincter of the rectum. There are slight discrepancies between domestic and foreign schools on this issue. The Parks classification (Parks, 1976) has been accepted throughout the world

- intrasphincteric fistulas

- transsphincteric fistulas (low, high)

- suprasphincteric fistulas

- extrasphincteric fistulas

Not to say that this difference is fundamental, but in my opinion, Parks’ classification is simpler and more logical, so we will continue to focus on it.

The above figure, taken from a foreign manual, seemed to me to be the most visual for an unprepared reader. The pink “bowl” with numbers in the center of each picture is the anal canal and the wide ampulla of the rectum, the adjacent purple “drop” is the fibers of the internal sphincter, the fragmented purple “drop” located outward (similar to an earthworm) is the fibers of the external sphincter , and the space between them is the same intersphincteric space. The upper left figure shows the intrasphincteric variant of the location of the fistula tract, when it runs along the intersphincteric space, or in the submucosal layer, without affecting the fibers of the external sphincter. The upper right figure shows the transsphincteric version of the fistula tract, when it goes through a small (low) or large (high) portion of the fibers of the external sphincter. Below on the left is a suprasphincteric variant, which is not in the domestic classification, when the fistulous tract runs very deep, affecting almost the entire array of the external sphincter, as with the extrasphincteric variant, but then returns through the intersphincteric space to the crypt, into which its internal opening opens. The last, extrasphincteric variant of the location of the fistula tract, shown in the lower right figure, is characterized by the fact that it passes through the entire array of the sphincteric apparatus of the rectum and opens not into the crypt, but directly into the lower ampullary section of the intestine.

The simplest, most reliable and safest classical method of surgical treatment of fistulas is dissection or excision of the fistula tract into the intestinal lumen; accordingly, the complexity of the fistula is determined by this very moment: whether its excision into the intestinal lumen is possible without significant damage to the muscular apparatus or not. In many foreign articles and manuals, to simplify the presentation of material, rectal fistulas are divided into “low” (when excision into the lumen is possible) and “high” (they are complex). In relation to the Parkes classification, intrasphincteric and low transsphincteric variants of the location of the fistula tract can be called “simple”. High transsphincteric and suprasphincteric fistulas are classified as “complex” because their dissection is associated with very significant damage to the sphincteric apparatus, which determines the need to search for other surgical options that are more technically complex and associated with a much greater risk of unsatisfactory results (relapses of the disease) and complications. The numbers in the figure are the frequency of occurrence of one or another type of fistula, and it can be seen that approximately 70-75% are “simple” variants. Extrasphincteric fistulas are a big “headache” for modern colorectal surgery, since, in my opinion, a more or less adequate method of surgical treatment has not yet been proposed. This type of fistula (non-cryptogenic) is exclusively iatrogenic in nature and is extremely rare - no more than 5%.

The table below shows statistics on the treatment of fistulas at the St. Petersburg Center for Coloproctology, which I collected for a report at one of the specialized conferences (the years are a bit “bearded”, but I don’t have more recent data). 700 treated fistulas over 3 years is a fairly impressive figure, which very few hospitals in our country can boast of, but I draw the readers’ attention to the fact that only 26% of them were “complex” fistulas, i.e. about 60 per year. If we divide this figure by the number of experienced doctors admitted to this type of operation, then each surgeon operates on no more than a dozen truly problematic rectal fistulas per year. That is, even with such a flow of patients, it’s probably not worth boasting about the “colossal” experience. This, of course, is not an absolute, since it is possible to participate in each operation, if not as the author, then as an assistant or spectator, which also adds a lot of skills, but nevertheless, well illustrates one of the facets of the complexity of this problem.

How do rectal fistulas manifest themselves (clinical picture)?

There are 2 possible options for the course of chronic paraproctitis:

- actually fistulous form

- recurrent form

The classic fistulous form of the disease is manifested by regular purulent or sanguineous-purulent discharge from the external fistula opening, sometimes with periodic exacerbations when the fistulous opening on the skin temporarily closes, which is accompanied by the accumulation of pus, pain, with further breakthrough of pus through the external opening.

A rarer recurrent form of the disease occurs in waves: the patient suffers acute paraproctitis with a classic detailed picture (painful infiltration, fever, etc.), then is operated on as an emergency, after which the wound heals without the formation of fistulous openings, the patient does not present any complaints, but after some time (from several months to several years) everything repeats itself. Difficulties with this form of chronic paraproctitis are due to the fact that between relapses, due to the absence of fistulous openings, diagnosis is significantly difficult, which, in turn, complicates radical planned surgical treatment. From my own practice in this regard, I can give an example of a “record holder” who, over the course of several years, underwent 18 (!) operations for acute paraproctitis, including several radical ones, with excision into the lumen, for the 19th time he came into my field of vision , and it was possible to break this vicious circle only with the help of a drainage ligature, carried out after the next opening of the abscess (more about this technique in the article “Treatment of rectal fistulas”). After 3 months, a planned operation was performed and the patient has been living without relapses for 1.5 years (I am writing about this success with caution, since the period is still very short).

Separately, we can dwell on incomplete rectal fistulas, which occur with a blurred clinical picture: discomfort in the anus, humidity, irritation and itching of varying degrees of intensity, which bother the patient periodically or constantly. During a visual examination during anoscopy, it is very difficult to see the internal opening, so diagnosing this pathology presents significant difficulties both in terms of symptoms and in terms of instrumental examination.

Methods for diagnosing rectal fistulas

In the vast majority of cases, making a diagnosis of “rectal fistula” based on the characteristic clinical picture and the presence of an external fistula opening does not present any particular difficulties. Nevertheless, additional instrumental and hardware diagnostic methods are very important. Why? There are two main reasons for their use: maximum preoperative clarification of the topography of the fistula tract for selection of a treatment regimen and differential diagnosis.

The mandatory diagnostic minimum for examining patients with chronic paraproctitis includes:

- probing of the fistula tract

- staining the fistula tract

- anoscopy

- sigmoidoscopy

- sphincterometry

Additionally the following can be used:

- fistulography

- transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)

- MRI of the pelvis

- colonoscopy

Probing the fistula is the main method of obtaining information about its topography. A button surgical probe is a thin metal needle with a diameter of 1.5-2.5 mm, with special rounded thickenings at the ends, which reduce the likelihood of making a “false move” during the examination. It is made of fairly soft metal, which allows it to be bent at the desired angle if necessary. The surgeon’s task is to insert a probe into the external opening of the fistula and try to guide it to the internal opening, assessing the presence of cavities, additional passages, and relation to the muscle sphincter. The photographs shown at the beginning of the article and in this section show the final result of this procedure: it looks scary, but in practice the procedure is unpleasant, but not painful, and is performed without pain relief. Probing a fistula is a simple and fairly informative diagnostic procedure, especially in experienced hands, but it has obvious disadvantages. Firstly, suprasphincteric fistulas (I remind you that according to statistics they occur in at least 20% of cases) are impossible to pass through with a probe due to their pronounced bend. Secondly, it is not always possible to determine the presence of additional passages and purulent leaks. Moreover, it is not always possible to even localize the internal opening of the fistula, which is a fundamental point.

If you have difficulty finding the internal opening, you can paint over the fistula by injecting a solution of brilliant green, methylene blue, or Betadine through the external opening. For better distribution of the drug, it is usually mixed with 3% hydrogen peroxide. After the injection of the dye, a standard anoscopy is performed, during which the surgeon sees the flow of dye from the internal fistula opening.

In principle, the information obtained may be quite sufficient to make a decision on choosing one or another method of surgical treatment of a fistula. But, taking into account the problems described above with diagnostics using classical probing and staining of the fistula tract, additional examination in the form of fistulography, TRUS or MRI is currently considered “good form”. These studies make it possible to more adequately assess the presence of purulent cavities, leaks and additional fistulous tracts, and TRUS and MRI - to assess the degree of involvement of the rectal sphincter apparatus in the process.

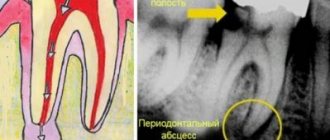

Fistulography is the oldest classical method of examining fistulas, in which a radiopaque contrast agent is injected into the fistula tract, after which a series of x-rays are taken. The technique is simple and cheap, but, in my opinion, inferior in diagnostic value to competitors. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis is potentially the most informative method, but also the most expensive, so its use for diagnosing fistulas is, in a sense, “shooting sparrows with a cannon.” Transrectal ultrasound, much more accessible and cheaper, while inferior in quality of detail, nevertheless allows one to obtain the data the surgeon needs about the fistulous course. There are already many comparative articles in medical periodicals in which no significant advantages of MRI over TRUS are found in relation to rectal fistulas (although in fairness, there are approximately the same number of articles that quite reasonably state the opposite). At our institution, we prefer TRUS and are quite pleased with the results. The photo below shows an ultrasound image of a rectal fistula. For example, there were more interesting pictures available, but this particular one well illustrates one of the problems of TRUS and MRI - to understand this wild and chaotic accumulation of pixels on the screen, you need considerable experience, and in St. Petersburg there are not many doctors who can adequately interpret the obtained data and transmit it to the surgeon.

The remaining methods are used for differential diagnosis, which we have already touched upon earlier. A complete list of diseases with which chronic paraproctitis needs to be differentiated is given below:

- specific infections, primarily actinomycosis

- tumor processes

- inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), primarily Crohn's disease

- pararectal cysts and teratomas

- epithelial coccygeal duct

- osteomyelitis of the pelvic bones

Most of the diseases on the list are extremely rare, or extremely rarely have points of intersection with fistulas. Only IBD, which often occurs in fairly young people, deserves maximum attention. It is for their diagnosis that a sigmoidoscopy is necessarily performed, and in the presence of specific complaints or due to age, a colonoscopy is additionally performed.

In domestic clinical guidelines, sphincterometry is recommended as a mandatory procedure, but this is more likely not for therapeutic needs, but “for the prosecutor.” Measuring the initial tone of the obturator apparatus of the rectum can be a starting point in further discussion about why the patient is bothered by incontinence after surgery.

Treatment of rectal fistulas

Since the issue of choosing a method for treating rectal fistulas is very large-scale, it was included in a separate article. Here I would only like to note that fistulas are treated exclusively with surgical methods of varying degrees of trauma. Just taking pills and anointing yourself with some “super ointment” sometimes even helps, but, unfortunately, not for long.

What happens if a rectal fistula (complications of chronic paraproctitis) is not treated?

This question arises in many patients, especially with complex variants of fistulas, for whom you begin to vividly describe their happy future and prospects for the next six months to a year when starting treatment. And this question, it should be noted, is really not simple. Rectal fistula is not a life-threatening disease, so “criminal” health problems should not happen if you refuse radical treatment. If you do nothing at all, then the future prospects are to constantly pour pus on your underwear, which is fraught with understandable problems with personal hygiene and sex life. The most unpleasant thing is the previously described situations, when the external opening is temporarily closed, and the patient experiences a condition very close to acute paraproctitis, as a rule, in the most inappropriate periods of life (vacation, business trip, “achtung” at work, etc.), those. life, as they say, is “on a powder keg.” Moreover, with each such episode there is a possibility that the purulent process will become more widespread, with the formation of additional leaks and fistula tracts, i.e. the fistula will become more difficult to treat further.

The most adequate alternative option for “refuseniks” is a drainage ligature. This method will be discussed in more detail in other articles about fistulas, but in short, a silicone ring is pulled through the fistula tract, which in foreign articles is often compared to piercing. Prolonged drainage of the fistula tract minimizes purulent discharge and prevents episodes of pus accumulation. Most often, this treatment option is used as preparation for a planned radical operation, and permanent drainage as an alternative to surgery is a very difficult idea for domestic surgeons to digest... In this regard, the experience of the British St. Mark's Hospital is interesting - a clinic originally (during the First World War) created as a hospital specializing in the treatment of rectal fistulas, i.e. having truly unique experience in this matter. Unfortunately, I never got the chance to study there myself (it’s long, expensive, you need a separate visa, etc.), but several good friends managed to visit there. According to their stories, if a surgeon assesses the risks of surgical treatment of recurrent, complex, etc. fistulas as very high, offering the patient permanent drainage as an alternative is absolutely not a shameful and normal option. For me, to be honest, this was also a big revelation, but now I am seeing 2 patients with complex iatrogenic fistulas who have been living with drainage ligatures (setons) for more than 2 years, periodically come for follow-up examinations, feel quite comfortable and so far have no desire to undergo surgery.

Conclusions and advice

The topic of chronic paraproctitis is very large-scale, and this rather large text can be considered just a small introduction, when writing which I wanted to convey to readers several main points. Firstly, rectal fistulas are a complex problem, even taking into account the fact that in 75% of cases patients are concerned about “simple” variants of the disease, since in order not to make a mistake and understand that the fistula is really “simple”, considerable experience is also needed . Secondly, fistulas are treated only by surgical methods, with the exception of attempts to seal the fistula tract, but the results of these experiments are still very far from ideal. The rest of the advice can be read in the next article - “Treatment of rectal fistulas.”

Sincerely, Anatoly Ivanovich Nedozimovany, associate professor of the course of coloproctology at Pavlov State Medical University of St. Petersburg.

Symptoms of the disease

General characteristics:

- the temperature rises to subfebrile;

- lack of appetite;

- weakness;

- pain;

- the presence of various discharges from fistulas.

Rectal fistula:

It occurs as a result of paraproctitis, it can be intra, trans, extrasphincteric.

The symptoms of the disease are as follows:

- hyperemia of the skin around the anus;

- pain in the anus area;

- bowel dysfunction;

- the presence of discharge from the rectum of various types (pus, mucus);

- deformation of the anus;

- sphincter functions are impaired.

What complications can there be?

A fistula on the gum of a tooth is a constant inflammatory process, open and unsafe, which has a very strong effect on the human body. The immune system works to suppress infection while pathogens, viruses, and other diseases invade various systems.

Lack of timely treatment destroys bone tissue.

All the insides in the area of the affected tooth root begin to rot and leave the cavity through the fistula canal. The tooth, naturally, goes for extraction. But the problem is that after this, the teeth nearby will also be affected. Therefore, the problem must be quickly resolved by contacting a doctor.

In addition, regular discharge of pus leads to other damage to the body. Pus enters the gastrointestinal tract, creating a favorable environment for the development of pathogens. This is dangerous for human life and health, not to mention the fact that the immune system literally works into overdrive while chronic inflammation is present.

How to treat a fistula

Treatment of a fistula involves surgery. Drug treatment is used to relieve symptoms and speed up rehabilitation after surgery.

What types of surgery are used?

- laser cauterization;

- excision, followed by plastic surgery;

- excision followed by suturing;

- ligature method;

- fistula filling.

For what diseases is surgery contraindicated?

- infectious diseases;

- deterioration of general condition;

- blood clotting disorder;

- decompensation of chronic pathologies.

Diagnostics

Often the fistula is located between two teeth. To determine the localization of the pathological process in one of them, you will need to take an x-ray or computed tomography. Under anesthesia, a gutta-percha pin is inserted into the person, which is used for filling. With its help, X-rays determine what the fistula tract is and determine ways to solve the problem.

A fistula on the gum is easy to identify from a photo, but it needs to be dealt with only after a detailed diagnosis of the disease. All diagnostic procedures must be carried out using the latest equipment with accurate indicators.

The DENTEN clinic is known for such equipment. Experienced doctors and diagnosticians will make the correct diagnosis and be able to competently treat the disease that has arisen, significantly improving the patient’s quality of life.

How to treat a fistula after its removal

Inpatient treatment lasts a week. The patient is prescribed bed rest, special dietary nutrition, painkillers, as well as antibiotics to prevent bacterial infection, and, if necessary, laxatives.

Local therapy involves baths with an antiseptic solution.

With timely treatment, the prognosis is very favorable, the recovery period is 7-10 days, after which the patient can live as usual.

Our medical center will be happy to help patients with this problem; we have innovative equipment for surgical intervention. The price for examination and treatment of a fistula may vary depending on the chosen method; it can be clarified with our manager. Reviews from satisfied patients are very positive and indicate trust in our clinic and doctors. Do not delay in seeing a doctor, take care of your health.

Fistula on the gum: treatment for periodontitis

As we said above, the appearance of a fistula during periodontitis is always associated with the formation of a deep periodontal pocket, from which the outflow of purulent discharge is disrupted.

In this case, a periodontal abscess is first formed in the projection of the pocket, in the center of which a fistula with purulent discharge can then form. Treatment will begin with a targeted or panoramic x-ray. The first aid when a patient visits a dentist will be to create a good outflow of pus from the periodontal pocket. To do this, under local anesthesia, they pass with a special instrument along the surface of the root, or additionally make a small incision in the gums in the projection of the day of the periodontal pocket. Antibiotics and antiseptic rinses are prescribed. But this is only an emergency, and not the main part of treatment. The main treatment will depend on the form of periodontitis, which can be either localized or chronic generalized.

Treatment of localized periodontitis –

If periodontitis occurs in only a few teeth (from 1 to 3), then it is called localized. The reasons for its occurrence may be the overhanging edge of a filling or artificial crown, injuring the gums, or the presence of a traumatic bite between the upper and lower teeth in some part of the dentition. The most important point in treatment is the elimination of the traumatic factor that caused the inflammation. This could be removing the overhanging edge of a filling, replacing a low-quality crown, grinding supercontacts between the upper and lower teeth, etc.

It may be necessary to remove the nerve from the tooth and fill its root canals. This is certainly necessary when the depth of the periodontal pocket reaches 2/3 of the length of the tooth root. The final stage of treatment is an open curettage of the periodontal pocket and the implantation of special materials to partially restore the level of bone tissue around the tooth.

Progress of open curettage operation –

Treatment of generalized periodontitis –

In the generalized form of periodontitis, periodontal pockets occur not in just a few teeth, but in almost all teeth. This form of periodontitis most often has a chronic course with sluggish symptoms, manifested by bleeding and soreness of the gums when brushing, redness and swelling of the gingival margin, tooth mobility, as well as purulent discharge from periodontal pockets during periods of exacerbation of the inflammatory process.

It is during periods of exacerbations that abscess formation can occur, i.e. formation of purulent abscesses in the area of deep periodontal pockets. The cause of the development of generalized periodontitis is pathogenic bacteria of dental plaque and tartar, which accumulate at the necks of teeth and under the gums as a result of irregular and/or insufficient oral hygiene. Treatment of generalized periodontitis will begin with the removal of dental plaque and anti-inflammatory therapy, and then, according to indications, curettage, splinting of teeth, and prosthetics may be recommended.

Unfortunately, patients rarely consult a doctor at the very beginning of the disease, and come mainly with moderate and severe stages of periodontitis, the treatment of which is very labor-intensive and already requires significant financial costs. You can also read about treatment methods for this disease at the link above.

Prevention of fistulas

The main measure for preventing fistulas is maintaining oral hygiene. It is necessary to undergo an annual examination by a dentist and, if necessary, begin treatment for caries and periodontitis in order to prevent the development of chronic diseases.

It is also advisable to be treated by experienced, qualified dentists, since poor-quality services can also lead to the formation of a fistula. After the intervention, you need to monitor your well-being to prevent the development of a fistula.

Postoperative care

In the postoperative period, all patients must undergo local and general anesthesia. Local anesthesia includes ointments and suppositories, which can locally reduce the severity of pain. Tablets, capsules, intravenous drugs are classified as general anesthesia. If the pain is significant, potent drugs (narcotic analgesics) are also used in a hospital setting. Your doctor will tell you the regimen for using painkillers, methods of administration, and specific names of drugs.

The average hospital stay is 1-5 days. It depends on the extent of the operation, the presence of complications and some other individual characteristics. During the postoperative period, you will undergo daily dressing changes and monitoring of wound healing. Antibacterial therapy is not indicated for all patients, but only if there are indications determined by the doctor. Mandatory wound care includes washing it with a stream of water at room temperature 3-4 times a day. This facilitates mechanical cleaning and will reduce the risk of infectious complications. The doctor will also show you how to properly perform dressings so that you can do them yourself at home.

Anesthesia

For surgical interventions in the perineal area, regional anesthesia is currently used. It includes subarachnoid (spinal) anesthesia at the lumbosacral level, which allows you to block the transmission of sensory and painful nerve impulses to the lower part of the body, including the anorectal area. In this case, the motor function of the lower extremities is not lost. Subarachnoid anesthesia is a fairly safe method and has a low risk of complications from the heart, respiratory system and nervous system. During the operation, for maximum comfort, the patient is conscious or in a state of medicated sleep (sedation). General anesthesia in anorectal surgery is used in individual cases at the discretion of the anesthesiologist-resuscitator.