CLASSIFICATION

Odontogenic infections (infections of the oral cavity), depending on the anatomical location, are divided into truly odontogenic

associated with damage to tooth tissue (caries, pulpitis);

periodontal

, associated with damage to the periodontium (periodontitis) and gums (gingivitis, pericoronitis), surrounding tissues (periosteum, bone, soft tissues of the face and neck, maxillary sinus, lymph nodes);

non-odontogenic

, associated with damage to the mucous membranes (stomatitis) and inflammation of the major salivary glands.

These types of infections can cause serious life-threatening complications from the cranial cavity, retropharyngeal, mediastinal and other localizations, as well as hematogenously disseminated lesions of the heart valve apparatus, sepsis.

Purulent infection of the face and neck

may be of non-odontogenic origin and includes folliculitis, furuncle, carbuncle, lymphadenitis, erysipelas, hematogenous osteomyelitis of the jaws.

Specific infections (actinomycosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, HIV) can also be observed in the maxillofacial area.

MAIN PATIENTS

Infections of the oral cavity are associated with the microflora that is constantly present here. Usually this is a mixed flora, including more than 3-5 microorganisms.

With truly odontogenic

infections, along with facultative bacteria, primarily viridans streptococci, in particular (

S.mutans, S.milleri

), anaerobic flora is released:

Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Fusobacterium

spp.,

Actinomyces

spp.

In case of periodontal infection, five main pathogens are most often isolated: P.gingivalis, P.intermedia, E.corrodens, F.nucleatum, A.actinomycetemcomitans

, less commonly

Capnocytophaga

spp.

Depending on the location and severity of the infection, the patient’s age and concomitant pathology, changes in the microbial spectrum of pathogens are possible. Thus, severe purulent lesions are associated with facultative gram-negative flora ( Enterobacteriaceae

spp.) and

S.aureus

.

In elderly patients and hospitalized patients, Enterobacteriaceae

spp also predominate.

In the conditions of domestic bacteriological laboratories, it is quite difficult to isolate a specific pathogen of a certain odontogenic infection. However, it seems possible to localize pathogens that play a major role in the development of oral infections in supragingival and subgingival plaque.

PRINCIPLES OF TREATMENT OF INFECTIONS OF THE ORAL CAVITY AND MAXILLOFACIAL AREA

Treatment of odontogenic infection

often limited to local therapy, including standard dental procedures.

Systemic antibacterial therapy is carried out only when odontogenic infection spreads beyond the periodontal period (under the periosteum, into the bones, soft tissues of the face and neck), in the presence of elevated body temperature, regional lymphadenitis, and intoxication.

When choosing antimicrobial therapy in a hospital setting, in cases of severe purulent infection, it is necessary to take into account the possibility of the presence of resistant strains among anaerobes such as Prevotella

spp.,

F. nucleatum

to penicillin, which determines the prescription of broad-spectrum drugs, amoxicillin/clavulanate in monotherapy or a combination of fluoroquinolone with metronidazole.

Due to increasing levels of resistance by Streptococcus

spp.

to tetracycline and erythromycin, these drugs can only be used as alternatives. Since metronidazole has moderate activity against anaerobic cocci ( Peptostreptococcus

spp.), simultaneous administration of β-lactam antibiotics is necessary to increase effectiveness.

Preventive systemic use of AMPs when performing dental procedures in the oral cavity or periodontium does not guarantee a reduction in the incidence of infectious complications in somatically healthy patients. Convincing data on the sufficient effectiveness of topical antibiotics for oral infections have not been obtained. At the same time, oral bacteria are a reservoir of determinants of resistance to AMPs. Excessive and unjustified use of antibiotics contributes to their appearance and the development of resistance of pathogenic microflora.

ODONTOGENIC AND PERIODONTAL INFECTION

PULPITIS

Main pathogens

Viridans streptococci ( S. milleri

), non-spore-forming anaerobes:

Peptococcus

spp.,

Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Actinomyces

spp.

Choice of antimicrobials

Antimicrobial therapy is indicated only in case of insufficient effectiveness of dental procedures or spread of infection into surrounding tissues (periodontal, periosteal, etc.).

Drugs of choice

: phenoxymethylpenicillin or penicillin (depending on the severity of the disease).

Alternative drugs

: aminopenicillins (amoxicillin, ampicillin), inhibitor-protected penicillins, cefaclor, clindamycin, erythromycin + metronidazole.

Duration of use

: depending on the severity of the current (at least 5 days).

PERIODONTITIS

Main pathogens

Microflora is rarely detected in the periodontal structure and is usually S.sanguis, S.oralis, Actinomyces

spp.

In periodontitis in adults, gram-negative anaerobes and spirochetes predominate. P.gingivalis, B.forsythus, A.actinomycetemcomitans and T.denticola

are highlighted most often.

In juveniles, there is rapid involvement of bone tissue in the process, with A. actinomycetemcomitans

and

Capnocytophaga

spp.

P.gingivalis

is rarely isolated.

In patients with leukemia and neutropenia after chemotherapy along with A. actinomycetemcomitans

C.micros

is isolated , and in prepubertal age -

Fusobacterium

spp.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice

: doxycycline; amoxicillin/clavulanate.

Alternative drugs

: spiramycin + metronidazole, cefuroxime axetil, cefaclor + metronidazole.

Duration of therapy

: 5-7 days.

For patients with leukemia or neutropenia after chemotherapy, cefoperazone/sulbactam + aminoglycosides are used; piperacillin/tazobactam or ticarcillin/clavulanate + aminoglycosides; imipenem, meropenem.

Duration of therapy

: depending on the severity of the course, but not less than 10-14 days.

PERIOSTITIS AND OSTEOMYELITIS OF THE JAWS

Main pathogens

With the development of odontogenic periostitis and osteomyelitis, S. aureus

, as well as

Streptococcus

spp., and, as a rule, anaerobic flora prevails:

P.niger, Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Bacteroides

spp.

Specific pathogens are less commonly identified: A.israelii, T.pallidum

.

Traumatic osteomyelitis is often caused by the presence of S.aureus

, as well as

Enterobacteriaceae

spp.,

P.aeruginosa

.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice

: oxacillin, cefazolin, inhibitor-protected penicillins.

Alternative drugs

: lincosamides, cefuroxime.

When P.aeruginosa

, antipseudomonas drugs (ceftazidime, fluoroquinolones) are used.

Duration of therapy

: at least 4 weeks.

ODONTOGENIC MAXILLARY SINUSITIS

Main pathogens

The causative agents of odontogenic maxillary sinusitis are: non-spore-forming anaerobes - Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Bacteroides

spp., as well as

H.influenzae, S.pneumoniae

, less often

S.intermedius, M.catarrhalis, S.pyogenes

.

Isolation of S.aureus

from the sinus is characteristic of nosocomial sinusitis.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice

: amoxicillin/clavulanate. For nosocomial infection - vancomycin.

Alternative drugs

: cefuroxime axetil, co-trimoxazole, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol.

Duration of therapy

: 10 days.

PURULENT INFECTION OF SOFT TISSUE OF THE FACE AND NECK

Main pathogens

Purulent odontogenic infection of the soft tissues of the face and neck, tissue of deep fascial spaces is associated with the release of polymicrobial flora: F. nucleatum

, pigmented

Bacteroides, Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Actinomyces

spp.,

Streptococcus

spp.

ABSCESSES, PHLEGMONS OF THE FACE AND NECK

Main pathogens

With an abscess in the orbital area in adults, a mixed flora is released: Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Bacteroides

spp.,

Enterobacteriaceae

spp.,

Veillonella

spp.,

Streptococcus

spp.,

Staphylococcus

spp.,

Eikenella

Streptococcus

spp.,

Staphylococcus

. predominate in children .

The causative agents of abscesses and phlegmon of non-odontogenic origin, most often caused by minor skin lesions, are S.aureus, S.pyogenes

.

With putrefactive-necrotic phlegmon of the floor of the mouth, a polymicrobial flora is released, including F.nucleatum, Bacteroides

spp.,

Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Streptococcus

spp.,

Actinomyces

spp.

S.aureus

can be isolated in patients with severe disease (more often in patients suffering from diabetes and alcoholism).

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice:

inhibitor-protected penicillins (amoxicillin/clavulanate, ampicillin/sulbactam), cefoperazone/sulbactam.

When P.aeruginosa

- ceftazidime + aminoglycosides.

Alternative drugs:

penicillin or oxacillin + metronidazole, lincosamides + aminoglycosides of the II-III generation, carbapenems, vancomycin.

Duration of therapy:

at least 10-14 days.

BUCCAL CELLULITE

Main pathogens

Usually observed in children under 3-5 years of age. The main pathogen is H. influenzae

type B and

S. pneumoniae

.

In children under 2 years of age, H. influenzae

is the main pathogen, and bacteremia is usually observed.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice

: amoxicillin/clavulanate, ampicillin/sulbactam, third generation cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftriaxone) IV, in high doses.

Alternative drugs

: chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole.

Duration of therapy

: depending on the severity of the current, but not less than 7-10 days.

LYMPHADENITIS OF THE FACE AND NECK

Main pathogens

Regional lymphadenitis in the face and neck is observed with infection in the oral cavity and face. Localization of lymphadenitis in the submandibular region, along the anterior and posterior surfaces of the neck in children aged 1-4 years, is usually associated with a viral infection.

Abscess formation of lymph nodes is usually caused by a bacterial infection. With unilateral lymphadenitis on the lateral surface of the neck in children over 4 years of age, GABHS and S.aureus

.

Anaerobic pathogens, such as Bacteroides

spp.,

Peptococcus

spp.,

Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

F.nucleatum, P.acnes

, can cause the development of odontogenic lymphadenitis or inflammatory diseases of the oral mucosa (gingivitis, stomatitis), cellulite.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice: AMPs corresponding to the etiology of the primary source of infection.

The extreme importance of infectious pathology in the modern world, with its high mobility and economic interdependence, lies in its global danger to the public health of each individual country and the entire world community as a whole. A comprehensive assessment of the risks to public health caused by infectious agents conducted by WHO international experts led to the conclusion that the current situation in the world is far from stable. Population growth, rapid urbanization and globalization, environmental degradation, the rapid introduction of new forms of health care, and the unjustifiable large-scale use of antimicrobial drugs have led to disruption of the delicate balance in the microbiological community. At the turn of the 20th-21st centuries, we witnessed unprecedented rates in history of the emergence of “new” diseases (at least 1 nosology per year!), the spread of infectious diseases with atypical clinical manifestations (25-57%) and “returning” infections (diphtheria, tuberculosis , syphilis, etc.), which, of course, determined the severity of the problem of infectious safety in the modern world [2, 22].

It is our firm belief that a solution to this problem can only be found jointly with the involvement of specialists from different fields of knowledge. After all, the essence of infectious pathology as a medical problem lies not only in the risk of epidemics and the aggravation of the course of acute infectious diseases. Today it is no secret that long-term persistent infections with scanty clinical manifestations are coming to the fore, the pathogens of which play an etiological or trigger role in the development of hematological, oncological, neurological, dental diseases, kidney damage, liver, joints, etc. [7, 8, 12, 15-18, 21, 23]. The need for a deep understanding of the issues of infectious pathology and infectious safety by doctors of various specializations is an urgent, vitally important problem.

From this point of view, dentists occupy a special niche, given the prevalence of dental diseases among people of all age groups (56-99% of the population) and the massive number of people seeking dental care. The unique quantitative and qualitative composition of the oral microflora and the intensification of modern dentistry extremely increase the risk of cross-infection of patients and professional infection of medical workers. Achieving sanitary and epidemiological well-being in medical dental institutions at the outpatient and hospital level can only be achieved by combining the efforts of dentists and infectious disease specialists in the study of infection-associated pathology. This is consistent with the statement of the American Dental Association (2012): “Dental care is an integral component of general health care. By improving the quality of dental services, we improve the public health and well-being of the nation.”

Currently, the proportion of people with a burdened premorbid background among dental patients reaches 93.3%. The most common among them are people with infectious pathologies (acute and chronic purulent-septic diseases, viral hepatitis, herpes virus infection, HIV infection, mycoses, etc.), food and drug allergies, often suffering from acute respiratory viral infections (ARVI), etc. Moreover, in most cases, patients do not even suspect that they have a particular disease, and in the time pressure of a dental appointment, it is extremely difficult for a doctor to obtain comprehensive information about the patient’s health status. Therefore, any patient who seeks dental care should be considered by a dentist as posing an epidemiological danger, regardless of the degree of risk of infection!

According to participants at the WHO Informal Network on Infection Prevention and Control in Health (2008), health care-associated infections (HAIs) represent a major public health problem and a significant burden for patients and health care workers, affecting all countries [6 ]. HAI refers to a hospital-acquired infection (HAI), which the WHO European Office defines as “any clinically significant infectious disease that affects a patient as a result of his admission to a health care facility or seeking medical care or employees of a health care facility as a result of their work in this institution outside depending on the appearance of symptoms of the disease during or after a stay in a medical facility” [16].

Of the main groups of nosocomial infections in dentistry, the most relevant are infections of surgical wounds and bloodstream [6], which develop as a result of a blood-contact transmission mechanism (through medical procedures) or a contact mechanism in which pathogens are localized on the skin and its appendages, the mucous membrane of the eyes, and the oral cavity. , the wound surfaces of one patient, infect another patient through direct contact or through contaminated objects in the hospital environment. It is necessary to remember the possibility of cross-infection of patients and professional infection of medical personnel as a result of the implementation of airborne droplets and contact mechanisms of infection transmission. The probable routes of transmission of infection from patient to patient during dental interventions are presented in the form of an epidemiological chain (Fig. 1, see color plate)

.

Rice.

1. Possible routes of transmission of infection from patient to patient during dental procedures. Modern factors contributing to the growth of nosocomial infections in dental practice include:

— the current epidemiological situation regarding HIV infection, viral hepatitis, herpes virus infections, etc.;

— distribution of consumption of parenteral psychotropic drugs;

— rapid growth of resistance of microorganisms to antimicrobial drugs up to multidrug resistance (for example, M. tuberculosis

, gram-negative bacteria);

— the spread of resistant strains among patients of a medical institution in the absence of effective infection control programs;

— widespread use of invasive methods of diagnosis and treatment;

— creation of large high-tech medical complexes with a specific microecology;

— difficulties in disinfecting and sterilizing complex medical equipment;

— unfavorable environmental situation;

— an increase in the number of patients with manifestations of secondary immunodeficiency.

Exogenous (primary) and endogenous (secondary) sources of infection during dental procedures are described. With exogenous infection, the source of infection is patients and medical personnel infected with pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms. Endogenous infection should be understood as activation of latent infection under the influence of stress (fear, exacerbation of chronic diseases, acute respiratory viral infections, etc.) and autoinfection, the etiological factors of which in 85% of cases are representatives of opportunistic flora [1, 4].

Endogenous infection deserves special attention, the ease of which is explained by the extremely rich auchthonous and allochthonous microflora of the mucosa, which varies significantly from person to person, as well as from one and the same person at different times. Representatives of the authentic microflora are resident microorganisms (from 160 to 300 species; up to 100 species can be isolated from 1 site, of which at least 30 species are permanently living) and transient microorganisms, the composition of which depends on environmental factors (consumed products and water, hygiene procedures, etc.). Representatives of the allochthonous flora enter the oral cavity from other microbiocenoses (from the intestines, nasopharynx, respiratory tract, etc.). As a result of research conducted in 2003, L.P. Zueva et al., it was shown that more than 1/3 of patients are carriers of Staphylococcus aureus

, 10% of strains of which are resistant to 5 or more antibacterial drugs

(Fig. 2, see color insert)

.

Rice. 2. Representatives of the microflora of the oral cavity, nose and pharynx, identified in patients who sought dental care in the department of maxillofacial surgery. According to the results of long-term studies by J. Prieto-Prieto, A. Calvo and T. Kuriyama et al., in the spectrum of odontogenic bacteria, Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella

and

Fusobacterium

, and Str. among aerobes

. viridians (Fig. 3, see color insert)

Rice.

3. Spectrum of odontogenic bacteria (Kuriyama et al., 2002; Prieto-Prieto J., Calvo A., 2004). [13, 19]. According to A.A. Zorkina et al. (2009), most often in inflammatory processes in the oral cavity, Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans

and

Porphyromonas gingivalis

, less often -

Bacteroides forsythus, Prevotella intermedia, Prevotella nigrenscens, Fusobacterium

spp.,

Peptococcus micros, Carnocytophaga

spp.,

Treponema denticola, Treponema sokranskii

.

Typical causative agents of odontogenic infections are Peptostreptococcus

spp.,

Peptococcus

spp.,

Fusobacterium

spp., periodontal infections are

A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, Pr.

intermedia, Eikenella corrodens, Fusobacterium nucleatum (especially in severe infections).

It is important for practicing physicians to remember that the diversity of microorganisms creates unique opportunities for the transmission of virulence and resistance determinants, the reservoir of which is the normal microflora [9, 20]. The possibility of exchanging genetic information between bacteria of the genitourinary tract and oral cavity, and in laboratory conditions, between taxonomically distant species of microorganisms has been described [9].

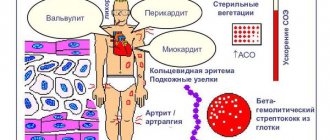

Infectious agents of oral tissues, from commesals to pathogens, play an etiological role not only in the initiation of dental diseases (caries, periodontitis, gingivitis, etc.). The integrity of the soft tissue barrier of the oral cavity, disrupted during dental procedures, injuries, and infections, leads to transient bacteremia (fungemia, viremia) and the entry of microorganisms into tissues that are not characteristic of them (for example, connective tissue, blood), as a result of which systemic changes in gene expression are induced, leading to to increase the virulence of infectious agents. Becoming endogenous pathogens, microorganisms can play a trigger role in the formation of pathologies of the digestive, respiratory, cardiovascular (DIC syndrome, infective endocarditis, atherosclerosis) systems, rheumatism, nephropathy, many infectious and allergic conditions, autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis - RA, Behçet and others) [10, 11, 20]. Thus, it has been proven that in S. sanguinis, S. oralis, S. mutans, S. salivarius

The constitutive expression of virulence genes is sufficient to induce fibrinogen binding by platelets, aggregation and thrombus formation when entering the bloodstream, and when deposited on altered or abnormally developed valves, lead to the development of infective endocarditis.

Changes in virulence can occur under the influence of genes regulated by the acidity of the environment into which microorganisms enter. Thus, with an increase in pH to 7.3-7.5, thrombin-like activity increases in S. gordonii

.

Upon contact with laminin and collagen of damaged heart valves, S. gordonii

triggers the expression of laminin-binding protein, which increases the adhesion of bacteria to the valve surface [11].

An interesting phenomenon is bacterial mimicry in representatives of the oral microflora. S. sanguinis cell wall protein epitope

- PAAP, associated with platelet aggregation, with an arthritic epitope of type II collagen, may be one of the causes of RA development.

The heat shock protein (HSP60) normally produced in humans is highly homologous to the bacterial HSPs of Mycobacterium

(HSP65),

S. sanguinis

(HSP65), and

Helicobacter pylori

(HSP60). The resulting antibodies cross-react with the development of a systemic inflammatory reaction and, through activation of the complement system, lead to immune inflammation in the vascular wall, arthritis, and Behçet's disease [14].

Infectious diseases, the source of which can be carriers of “classical” pathogens (hepatitis, HIV infection, tuberculosis, syphilis, herpes viruses, etc.), account for no more than 15% of all nosocomial infections in dental medical institutions. According to WHO (2007, 2010) [2, 6], among all infectious diseases, the most relevant for dentists and their patients are viral hepatitis A, B, C, D (TTV, G, SEN - ?), HIV infection, herpes virus infection , tuberculosis, candidiasis, acute respiratory viral infections and influenza, measles, legionellosis, mumps, streptococcal diseases (tonsillitis, scarlet fever), staphylococcal diseases (sore throat, pneumonia, enterocolitis, purulent lesions of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, etc.), diphtheria, syphilis, gonorrhea and tetanus . The main infectious diseases with clinical manifestations in the oral cavity are presented in the table

.

It should be recognized that the manifestations of even well-known infectious diseases can change against the background of the patient’s chronic diseases or during co-infection, acquiring features that are unusual for them, which complicates their clinical diagnosis and requires timely laboratory examination.

In addition to those presented in the table

infectious diseases, there is a large group of viral infectious diseases that do not have characteristic pathological manifestations in the oral cavity, but are transmitted by blood contact during dental interventions, which leads to the development of life-threatening diseases for patients and medical personnel (viral hepatitis B, C, D; cytomegalovirus infection; Epstein -Barr virus infection - except for infectious mononucleosis and herpes zoster described above; herpes virus infection caused by HHV-6, HHV-7, HHV-8 type, etc.).

All of the above indicates the great role of infectious agents in human pathology in general and in dental practice in particular. A dentist can meet with an infectious patient at any time. The life of the patient and the timely suppression of the epidemic process often depend on his erudition and knowledge, which makes it possible to prevent cross-contamination and infection of medical personnel when providing dental care.

NON-ODONTOGENIC AND SPECIFIC INFECTION

NECROTIC STOMATITIS (VINCINS ULCER-NECROTIC GINGIVOSTOMATITIS)

Main pathogens

Fusobacterium is concentrated in the gingival sulcus

, pigmented

Bacteroides

, anaerobic spirochetes. With necrotizing stomatitis, there is a tendency for infection to quickly spread into surrounding tissues.

The causative agents are F. nucleatum, T. vinsentii, P. melaninogenica, P. gingivalis and P. intermedia

.

In patients with AIDS, C. rectus

.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice:

phenoxymethylpenicillin, penicillin.

Alternative drugs:

macrolide + metronidazole.

Duration of therapy:

depending on the severity of the current.

ACTINOMYCOSIS

Main pathogens

The main causative agent of actinomycosis is A.israelii

, association with gram-negative bacteria

A. actinomycetemcomitans

and

H. aphrophilus

, which are resistant to penicillin but sensitive to tetracyclines, is also possible.

Choice of antimicrobials

Drugs of choice

: penicillin at a dose of 18-24 million units/day, with positive dynamics - transition to step-down therapy (phenoxymethylpenicillin 2 g/day or amoxicillin 3-4 g/day).

Alternative drugs

: doxycycline 0.2 g/day, oral drugs - tetracycline 3 g/day, erythromycin 2 g/day.

Duration of therapy

: penicillin 3-6 weeks IV, drugs for oral administration - 6-12 months.

results

In 29 cases (90.7%) the result of OA was sinusitis, in 2 - palatal abscess (6.2%) and canine fossa abscess (3.1%). The cervical-fascial spaces were involved as follows: submental space in 2 cases (16.7%), submandibular in 7 cases (58.3%), sternocleidomastoid region in 2 cases (16.7%), and peripharyngeal with descending spread into the mediastinum in one (8.3%).

Causes of OI included tooth extraction (7 cases - 15.9% overall), installation of implants (13 cases - 29.6%), caries (12 cases - 27.3%), eruption anomalies (8 cases - 18.2% ), endodontic manipulations (2 cases - 4.5%), as well as sinus lifting (2 cases -4.5%). They are also divided into complications of pre-implantology (2 cases - 4.5%) or implantology treatment (13 cases - 29.6%), consequences of “classical” dental procedures (i.e. tooth extraction, endodontics), caries or eruption anomalies ( 29 cases - 65.9%), according to the proposal of Felisati's classification [11].

Microbiological cultures of surgical specimens were negative in 5 cases (11.4%) or showed nonspecific growth of mixed oropharyngeal flora (OP) in 12 cases (27.2%). Thus, antibiotic therapy was used in most patients. Three (6.8%) purely mycotic infections (Aspergillus spp) were observed as mycetomas of the maxillary sinus.

Cervical surgical drainage with removal of necrotic tissue in combination with dental procedures aimed at eliminating concomitant dental pathologies was used in all cases of detection of oropharyngeal flora (12 cases). Recurrent infection developed in one case after surgery (ie, parapharyngeal abscess as a consequence of long-standing, untreated caries), with retropharyngeal and subsequent descending mediastinal spread. The patient required additional thoracotomy and an extended stay in the intensive care unit.

Conversely, in case of upper segment OI (32 patients), access was created through a functional endoscopic transnasal approach in 11 cases (34.4%) or using a combination of FEC and the Caldwell-Luc approach (18 cases - 56.2%). Three upper ROIs (two hard palate abscesses and one canine fossa abscess - 9.4%) were eliminated by transoral surgical drainage without FEC.