Dr. Chad Duplantis

Clinical dentistry is a series of processes and decisions that affect the quality of care provided. Cementation of indirect restorations is no exception, since there are several options in this area. This article will help doctors make the right decision when choosing a method of fixation of indirect restorations.

| Modified GICs | Self-adhesive composite cements | Adhesive composite cements |

| Meron Plus, Voco | Bifix SE, Voco | Bifix QM, Voco |

| RelyX Luting Plus, 3M | RelyX Unicem, 3M | RelyX Ultimate, 3M |

| Nexus RMGI, Kerr | SpeedCem Plus, Ivoclar Vivadent | Multilink Automix, Ivoclar Vivadent |

| GC FujiCem 2 | Maxcem Elite, Kerr | NX3 Nexus, Kerr |

Introduction

Dental cementation has undergone significant changes since zinc oxide eugenol cement was introduced in 1850. Manufacturers are constantly making minor changes to the composition, which leads to a huge variety of cements and complicates the process of choosing a material. With each generation comes new indications, recommendations, performance characteristics and technologies.

Just like fixation materials, indirect restorations themselves have also achieved significant development and diversity. Prosthetic dentistry has reached heights that the field's pioneers could never have imagined. However, failures can occur if the restoration is not properly worked or cemented. Even the type of restoration - inlay, crown, veneer - can have a significant impact on the choice of luting cement.

This article examines the most commonly used cements from the perspective of cementing the most popular restorations. The main goal is to simplify the process of choosing a fixation method and fixation material for practitioners. Conscious choice of materials allows you to achieve predictably good results.

| Restoration | Cement | Tooth preparation | Preparation of the restoration |

| Zirconium | Cement: good retention only | Ensure the stump is clean (pumice stone or brush) | Sandblast the restoration (50-60 µm aluminum oxide, |

| Bond: self-adhesive composite cement | Ensure stump cleanliness | Sandblast the restoration (50-60 µm aluminum oxide, | |

| Bond: adhesive composite cement | Ensure the stump is clean, etch and/or apply bonding in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations | Sandblast the restoration (50-60 µm aluminum oxide, | |

| Lithium silicate or disilicate | Bond: self-adhesive composite cement | Ensure stump cleanliness | Etch the restoration with 5% hydrofluoric acid for 20 seconds, apply primer, apply self-adhesive composite cement |

| Bond: adhesive composite cement | Ensure the stump is clean, etch and/or apply Bond in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations | Etch the restoration with 5% hydrofluoric acid for 20 seconds, apply primer, apply bonding agent, apply adhesive composite cement | |

| Leucite reinforced ceramics | Bond: adhesive composite cement | Ensure the stump is clean, etch and/or apply Bond in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations | Etch the restoration with 9.6% hydrofluoric acid for 1 minute, apply primer, apply bond, apply adhesive composite cement |

| Hybrid ceramics | Bond: adhesive composite cement | Ensure the stump is clean, etch and/or apply Bond in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations | Sandblast the restoration (25-50 µm aluminum oxide, 1.5-2 bar), apply primer for 60 seconds, apply bonding agent and adhesive composite cement (follow manufacturer's instructions) |

Cements

In the huge variety of nomenclature, there are three main types of cements, the most widely used in practice and recognized among dentists: chemical, adhesive and self-adhesive cements. Each of these types has not only its own indications, but also an individual protocol for achieving success.

It should be especially emphasized that there is no universal cement that satisfies all the requirements of any clinical situation, therefore knowledge in the field of materials science is necessary.

Chemical cements

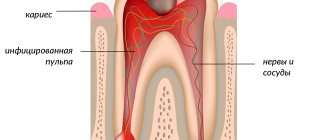

Chemical cements simply create a bonding layer between the tooth and the restoration. The bond is ensured by physical factors; chemical bonds (bonding) are not formed.

Modified GICs

Traditional GICs have been used in dentistry for over 40 years. But in 1990, composite-modified GICs were introduced for the first time. Modified GIC showed better properties in comparison with traditional ones due to the addition of methacrylate monomers. They have better bending strength, biocompatibility, and, being chemical cements, provide stronger fixation.

Modified GICs have a number of attractive properties for doctors: they release fluoride ion, do not require the application of an adhesive, and prevent the occurrence of postoperative sensitivity. They are indicated for many types of restorations, although there are reports of fractures in leucite and feldspathic porcelain cemented with MSIC. For successful fixation of prostheses using MSIC, it is necessary to ensure correct retention and stability.

Composite cements

Composite cements are a large group of materials, including many subcategories. The classification below is the most common in modern dentistry. The two main categories of composite cements are adhesive and self-adhesive composite cements.

Adhesive composite cements

Adhesive composite cements appeared earlier than self-adhesive ones. They have many indications for use and should be carefully studied before use. There are chemical, dual and light curing options. To ensure success, there is a detailed bonding protocol that includes pre-treatment of the tooth and the internal surface of the restoration.

Additionally, depending on the type of adhesive, an additional silane coupling agent may be required to bond to the restorative surface. Many shades are available, as well as samples (depending on the manufacturer).

Self-adhesive composite cements

SACCs are often called “universal cements.” Having an initial pH level of 2.1-2.3, they are able to etch the tooth, while the monomers included in their composition provide a bond to the tooth without applying a separate primer or bond (not recommended by most manufacturers). Most of these materials are dual-cured, and although the bond strength is not the same as that of adhesive cements, the bond strength is improved when light activated. Indications for use are extensive: crowns, bridges, inlays made of any materials. However, veneers are not recommended to be fixed using SACC, as color changes may occur as a result.

Glass ionomer cements (glass ionomers)

Glass ionomer cements (GIC) are a whole class of modern dental materials created by combining the properties of silicate and polyacrylic systems. Filling teeth using glass ionomer cements is gradually replacing zinc phosphate and zinc polycarboxylate cements from dental practice. Glass ionomer cements are usually classified according to a number of characteristics.

According to their application. For permanent fillings (aesthetic, reinforced), quick-hardening (for gaskets, fissure sealing), for filling root canals, for fixing orthopedic structures.

- By release form:

- powder-liquid (powder – finely dispersed aluminofluorosilicate glass with various additives, liquid – an aqueous solution of a copolymer of carboxylic acids with the addition of tartaric acid);

- powder (all components are in powder, which is mixed with distilled water; so-called Aqua cements);

- capsules (powder and liquid are packaged in capsules with a thin partition in the required ratio, so when mixed, glass ionomer cement with optimal properties is obtained);

- paste (in tubes or syringes); do not require mixing and harden when irradiated with a halogen lamp.

Depending on the chemical composition of the curing mechanism.

- Classic (powder-liquid). Finely dispersed aluminum fluorosilicate glass powder (particle sizes 20-50 microns). Powder components: silicon dioxide, aluminum oxide, calcium fluoride, fluorides of other metals (providing fluoride release for caries prevention), aluminum phosphate (providing strength and abrasion resistance), barium, zinc, strontium salts, etc. (providing radiopacity). The liquid is an aqueous solution of a copolymer of polycarboxylic acids (acrylic, itaconic, maleic) with the addition of a tartaric acid isomer. In the case of Aqua cements (only powder that is mixed with distilled water), polycarboxylic acids are included in the original powder in the form of crystals. In metal-containing glass ionomer cements, metal additives and alloys (silver-tin, silver-palladium) are additionally introduced into the powder composition. Hardening of classic glass ionomer cements occurs according to the type of ion exchange reaction (hence the name glass ionomer): hydrogen ions (present in an aqueous solution of polycarboxylic acids) exchange with metal ions (calcium, aluminum) of the glass, calcium and aluminum ions bind the hydroxyl groups of polycarboxylic acid chains (a matrix is formed metal polyacrylate containing unreacted glass particles). In the initial stage of hardening, calcium polyacrylic chains are formed quite quickly. This reaction ensures the cement sets and lasts for several minutes. However, the efficiency of binding by calcium ions is not high enough and in the early stages of hardening, calcium-polyacrylic chains can dissolve in water (therefore, the cement must be protected from moisture during this time). When the calcium ions have reacted, aluminum ions react and aluminum-polyacrylic chains are formed. The trivalent nature of aluminum (as opposed to the divalent nature of calcium) provides a higher degree of cross-linking and the formation of spatial structure. It is at this stage that the final cement matrix is formed. The completion of the second phase occurs in approximately 2-3 weeks (the curing process can be accelerated by the use of hybrid glass ionomers, which already gain sufficient strength within about 40 seconds at the initial stage of photopolymerization). Additionally, silica gel (strong structure) is formed on the surface of the glass particles. As a result, the final structure of hardened glass ionomer cement is glass particles surrounded by silica gel and located in a matrix of cross-linked polycarboxylic acid (metal polyacrylate) molecules.

- Hybrid glass ionomer cements (polymer modified glass ionomer cements). They have a double (chemical and light) or triple hardening mechanism. The powder is finely dispersed aluminosilicate glass (as in the case of classical glass ionomer cements), sometimes with the addition of polycarboxylic acid copolymer crystals (as in the case of Aqua cements). The liquid is an aqueous solution of a copolymer of polycarboxylic acids (acrylic, itaconic, maleic), the ends of the molecules of which are modified by the addition of unsaturated methacrylate groups (as in dimethacrylates of composite filling materials). The liquid also contains tartaric acid, hydroxyethyl methacrylate and camphoroquinone (a photoinitiator). The first stage of the curing mechanism is the binding reaction of the terminal unsaturated methacrylate groups of polycarboxylic acids due to the photoinitiated formation of terminal radicals (photopolymerization). The second stage is the usual classical reaction of cross-linking of polyacid macromolecules with metal ions. Hybrid glass ionomer cements (with a dual curing mechanism) have improved physicochemical properties, but also have a significant drawback: in areas inaccessible to light from a photopolymerizing lamp, curing occurs only due to a classical chemical reaction (which affects the physicochemical characteristics of glass ionomer cements) . Glass ionomer cements with a triple curing mechanism do not have this drawback (the first two stages are like double-curing glass ionomer cements, and the third stage is catalytically initiated polymerization of the terminal methacrylate groups of polycarboxylic acids without exposure to light).

This classification is conditional, since many modified glass ionomer cements have recently appeared: with the addition of polymer resins, with specially treated fine glass particles, etc.

A very important advantage of glass ionomer cements is good chemical adhesion to tooth tissues. This is believed to occur due to the formation of chelate bonds between the hydroxyl groups of polycarboxylic acids and calcium ions of the surface hydroxyapatite (similar to the classical chemical cross-linking reaction during the hardening of glass ionomer cements), as well as due to the formation of hydrogen bonds of carboxylate groups with collagen (an organic component of dental tissues).

Other advantages of glass ionomer cements include good chemical adhesion to other filling materials (including composites), high biological compatibility with tooth tissues, thermal expansion characteristics close to tooth tissues (which protects against violation of the marginal seal of fillings), low modulus of elasticity ( which allows the use of glass ionomer cements as spacers or a base for dental restoration with composite materials).

Glass ionomer cements have bioactivity, which is associated not only with chemical adhesion to tooth structures, but also with prolonged fluoride release and the release of other ions (aluminum, calcium, strontium; they contribute to the remineralization of tooth structures during carious lesions). All other restorative materials (for example, composites) are not bioactive and serve only to restore the shape and aesthetics of the tooth. During the initial period (about 2 days) of hardening of glass ionomer cements, fluoride ions are rapidly released, which remain free within the glass ionomer matrix. The free movement (diffusion) of fluoride ions is due to the fact that they are not structurally associated with the cement matrix and are capable of migration into the oral cavity and into the dental tissue adjacent to the restoration (filling), while providing a cariesostatic and antibacterial effect. The release of fluoride ions (in smaller quantities) continues over a long period (prolonged process, more than 1 year). The diffusion of fluoride ions into dentin and enamel causes increased mineralization of hard tooth tissues, a decrease in dentin permeability, remineralization of initial carious lesions and stopping or slowing down the remaining carious process. The hard tissue under glass ionomer cement turns out to be denser and hypermineralized. In addition, glass ionomer cements are capable of adsorbing (absorbing) fluoride ions upon contact with fluoride-containing materials (toothpastes, gels, rinses), which leads to re-enrichment of the glass ionomer restoration (filling) with fluoride ions. The incoming fluoride ions are then slowly released into the oral cavity and tooth tissue adjacent to the restoration (filling). Thus, glass ionomer cement acts as a reservoir (depot) of fluoride ions. In recent years, glass ionomer cements are increasingly used to seal fissures (primarily due to the remineralizing effect on the enamel in the fissure area due to fluoride release).

Typical representatives of modern glass ionomer cements are the following.

Fuji Plus is a composite-reinforced glass ionomer cement. Used for permanent cementation of metal, metal-ceramic and metal-composite crowns and bridges, inlays and onlays made of composites, ceramics and dental alloys.

Fuji I (Fuji I) is a glass ionomer cement for permanent cementation of orthopedic crowns, bridges, inlays, onlays made of any dental alloys.

Fuji IX (Fuji 9, Fuji IX) is a classic glass ionomer restoration (filling) cement of packable viscosity (the term “packable” means maintaining the shape given to the material even before the stage of its curing, which allows the dentist to easily carry out the preliminary modeling stage). Due to its high abrasion resistance, it is used for restorations (fillings) in the area of chewing teeth and reconstruction of the crown part of the tooth.

Fuji Lining is a light-curing glass ionomer cement. It has low shrinkage during hardening, therefore it is used as an insulating gasket.

Ionosit Baseliner is a light-curing hybrid glass ionomer cement (more often referred to as compomers). A one-component material that expands slightly when curing and is therefore used as an insulating spacer to compensate for polymerization shrinkage of composites. Physical properties are approximately 3 times stronger than traditional glass ionomer cements.

TimeLine is a light-curing glass ionomer material. Used as an insulating spacer for composite fillings (restorations).

CORE MAX is a glass ionomer cement reinforced with a composite (sometimes referred to as chemically cured composites). Particularly strong cement for restoring the crown of a tooth using pins. RelyX LUTING is a chemically cured hybrid glass ionomer cement. Used for permanent cementation of orthopedic crowns, inlays made of ceramics, metals, composites, cementation of bridges, root pins. Ionoseal is a light-curing glass ionomer cement. It has high tensile strength and compression resistance. Used for insulating gaskets (has good adhesion to composite materials). Vitremer is an aesthetic hybrid glass ionomer material with a triple curing mechanism (light polymerization, chemical polymerization, classical glass ionomer reaction). Used to restore the coronal part of the tooth for prosthetics, aesthetic filling and restoration.

A shining Hollywood smile from leading specialists in therapeutic dentistry. Make an appointment!

Restorations

According to the Glidewell laboratory, zirconia restorations (solid or layered) are in first place in popularity. In second place by a large margin are restorations made of lithium silicate or lithium disilicate. In third place are crowns based on precious and semi-precious metals. Each type has individual cementation characteristics.

Ceramics and glass ceramics

Many doctors mistakenly believe that ceramics and glass ceramics are the same thing. It is important to understand that ceramics are divided into three main categories: glass ceramics, partially filled glass ceramics, and polycrystalline ceramics. All these materials have specific properties and require an individual approach.

Glass ceramics itself

This type of ceramic is composed of feldspathic minerals and aluminum oxide. Typically, such ceramics are called feldspathic ceramics. Glass ceramics are highly aesthetic and can be used for crowns, veneers, inlays, etc.

Due to increased fragility, glass-ceramic restorations are recommended to be fixed using adhesive composite cements. For successful bonding, it is recommended to etch the inner surface of the restoration with 9.6% hydrofluoric acid for a minimum of 1 minute (maximum 2.5 minutes), then apply MDF primer for one minute and blow with air.

Partially filled glass ceramics

The CNS consists of different types and quantities of particles filling a glass matrix. The strength of these materials is due to the large number of particles embedded in the matrix and the smaller amount of glass matrix. There are three most well-known types: leucite-enhanced, lithium disilicate, and glass-infiltrated alumina. The strength of these types of ceramics increases from the first to the third, and depends on the filler of the glass matrix. These materials are indicated for the manufacture of crowns, veneers, and inlays.

All three types of materials are fixed differently:

- For leucite ceramics – etching with 5% hydrofluoric acid for one minute, adhesive cementation

- For lithium disilicate – etch with 5% hydrofluoric acid for 20 seconds

- For ceramics based on aluminum oxide – sandblasting with aluminum oxide or silicon oxide.

In my opinion, lithium disilicate and glass-infiltrated aluminum are ideal options for adhesive cementation (adhesive and self-adhesive cements). It is possible to cement such restorations with modified GIC; the use of a silane primer is not indicated.

Polycrystalline ceramics

Polycrystalline ceramics are densely sintered aluminum oxide or zirconium oxide. Zirconium oxide is the most popular material among dentists, according to Glidewell Laboratory. Restorations made from this material have many indications in dentistry, including full crowns. Both aluminum oxide and zirconium oxide are silicon-free and metal-free materials and therefore require different handling from conventional ceramics.

The retention elements of the stump play an important role in the choice of cement. Restorations can be cemented with conventional cement (modified GIC) if the core has good retention characteristics. Bonding is possible if the technology is followed. Dr. Marcus Blatz proposed a uniform concept for bonding zirconium restorations. The internal surface must be sandblasted using 50-60 micron aluminum oxide, under a pressure of 2 bar. The surface is then treated with a primer for zirconium or aluminum. The final stage is the application of dual- or chemical-curing composite cement. It is important not to use light-curing cement as it does not cure completely.

Hybrid ceramics

Hybrid ceramic, first introduced in 2012, is the newest material for the fabrication of indirect restorations. There are several materials of this type. All of them consist of ceramic particles embedded in a composite matrix, up to 80% full. Each manufacturer lists different indications, but all materials in this group are suitable for making crowns, veneers, inlays and implant crowns.

These materials are attractive to CAD/CAM users because they are quickly produced and do not require firing. Each material has a unique bonding protocol. Compliance with this is extremely important for reliable adhesion. Due to variations in composition, it is necessary to strictly follow all manufacturer's recommendations to achieve excellent results.

For luting, I recommend using a dual-curing adhesive composite cement, as these cements work well with hybrid ceramics. Sandblasting is necessary, but hydrofluoric acid is contraindicated for most restorations of this type.

Metal-based restorations

Metal-based restorations have fallen out of favor in modern dentistry (Glidewell Dental Laboratories, 2018). Although there are some variations in metal restorations, they can be cemented in a manner similar to aluminum or zirconium-based restorations. Modified GIC or dual- or chemical-curing composite cements can be used with equal success. When using composite cement, the need to use a primer for the metal is controversial, but no adverse effect has been observed from its use.

Trends in luting methods for indirect restorations

Dr. Sam Simos

In recent years, indirect restorations have become more and more in demand among patients, and this demand has led to the further development of dental prosthetics. There was a demand among patients for highly aesthetic denture materials that do not have metal frames, and dentists gave patients what they asked for. At the same time, the emergence of new restorative materials, adhesive systems and cements has introduced confusion and complexity into the treatment process. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of available cements and adhesive systems, as well as optimal schemes for their use.

Cementation or adhesion: what to choose?

Very often, specialists, when talking about fixation of indirect restorations, use the terms “cementation” and “adhesion” as synonyms, but in fact the difference between these concepts is significant. Cementation refers to a process in which mechanical retention is achieved using cement. While adhesion can be defined as the joining of two dissimilar materials either mechanically or through chemical bonds. Bonding is the process of joining materials together. This distinction is made for the sole purpose of demonstrating the superiority of the adhesive approach in bonding strength when fixing dissimilar materials (for example, tooth and crown).

Rice. 1. Scheme for choosing cement depending on the height of the stump and its taper

For many years, metal was the only material on the dental market, requiring only one type of luting cement to be stocked in the clinic. The emergence and widespread use of new materials based on zirconium (Lava, 3M) and lithium disilicate (IPS e.max Ivoclar Vivadent), which occurred in 2001 and 2005, respectively, required the development of new materials and technologies for their fixation. Soon after the use of these materials began, it became apparent that the use of traditional methods was often inappropriate. The chemistry of lithium zirconium disilicate is so different from current metal and metal-framed crowns that different adhesive protocols and materials must be used. In particular, the surface of lithium zirconium disilicate is hydrophilic and has high energy, which is bad for adhesion. Therefore, a step was needed to prime the surface of the restoration so that it becomes hydrophobic and has low energy, in which case the cement can bond reliably to it. This is achieved by applying a special primer to the inner surface of the crown before fixation and subsequent drying. Typically, for this purpose, silane is used for lithium disilicate, and for zirconium, a special primer is used (for example, Z-PRIME Plus, Bisco Dental Products), produced by many manufacturers. A universal primer has recently been introduced (Monobond Plus, Ivoclar Vivadent) that can be used for metal, metal-framed crowns and all-ceramic restorations, including leucite ceramics (such as IPS Empress Esthetic, Ivoclar Vivadent) as well as other high-strength ceramics such as disilicate lithium (IPS e.max or Initial LiSi Press, GC America) and high-strength polycrystalline ceramics such as zirconium.

Currently, the adhesive protocol includes the following procedures: the tooth must be prepared, etched, and an adhesive suitable for the clinical case must be applied to the tooth. Whatever cement is used, the restoration must be treated with an appropriate primer, because only in this case will the cement be able to reliably unite the tooth and the crown material. Although the procedures seem simple, the geometry of the tooth core, the availability of different materials for making crowns, and the many options for choosing cement can confuse even advanced specialists.

Other factors relevant to increasing the service life of a restoration

Clinicians must understand that the geometry of the core and the preparation procedure itself are of equal importance to other factors when bonding new restorative materials to the tooth. To achieve long service life, a core geometry that can provide good retention is as important as the luting cement. The height and taper of the stump are important, since they determine how well the cement will withstand lateral loads during the service life of the restoration.

For good long-term results, high-quality isolation of the surgical field, which can be provided by a rubber dam or other isolation means (for example, Isolite, Isolite Systems), is also key, otherwise the physical properties of the adhesive and cements may be compromised.

Rice. 2. The tooth stump is short. The crown was prepared for cementation. The total etching technique was used. The cement used was Calibra Ceram (Dentsply Sirona).

Rice. 3. Total etching with phosphoric acid Uni-Etch W/BAC 32% (BISCO Dental Products)

Rice. 4. Application of Prime & Bond adhesive (Dentsply Sirona)

Rice. 5. Primer BruxZir Zirconia (Glidewell Laboratories) was added to the crown.

Rice. 6. Adding Calibra Ceram cement to the crown

Rice. 7. The crown is installed on the tooth

Rice. 8. Excess cement was removed after pre-light curing.

Choice of cement

Once the tooth and restoration surface are prepared for cementation, the final step is to apply the cement appropriate to the situation.

The main purpose of cement is to fill the microgap between the crown and the tooth. Another important function is the cementation of the restoration. Nowadays, the clinician has a large selection of cements, from those providing only mechanical retention to adhesive ones, which hold the restoration both mechanically and with the help of chemical bonds. This diversity often leads to understandable confusion about what to choose in a particular clinical situation and how best to use the selected cement. In fact, the choice is influenced by the geometry of the tooth stump (retention properties of the tooth stump and ability to resist loads), the clinical situation and the preferences of the clinician. It is important to note here that if the tooth is prepared unsatisfactorily, little will depend on the choice of cement.

Now let's look at what cements are available to us for fixation.

Glass ionomer cement

Glass ionomer cements (GICs) were introduced to the market in the 1970s. This is traditional cement, which has such properties as a thin film of cement, is not afraid of microleakage and has anti-caries activity due to the release of fluoride. Cements of this group are chemically cured and are indicated for fixation of metal crowns, structures with a metal frame, as well as all-ceramic restorations, in situations where the tooth core can provide good retention and resistance to loads. Since GIC has been in use for a long time, it is well studied and is an extremely reliable cement when used correctly.

Glass ionomer cements modified with composite

Composite-modified glass ionomer cements (GICMCs) appeared on the market in the 1990s and are a hybrid of GIC and composite cements (CCs). GICs have the advantages of traditional GICs, but also have increased strength and ease of use due to their reinforcement with a composite matrix. SICMK are insoluble in oral fluid and can be light-cured. Indications for their use are metal orthopedic structures, structures with a metal frame, as well as restorations made of lithium and zirconium disilicate, if control of microleakage during fixation is difficult. However, it is worth noting that these cements are indicated in the case of a tooth stump geometry that promotes retention, since even the latest generation SICMs cannot compare in strength with composite cements.

Composite cements

Composite cements were commercially available in the 1980s but have only recently become popular after significant development. These are adhesive cements and their versatility and bonding strength make these cements the best choice for luting today. However, it should be noted that clinicians must be able to work with this group of cements as applicable to a specific clinical situation, otherwise their effectiveness will be reduced. Composite cements are divided into three subgroups: chemical-curing, light-curing and dual-curing cements. It should be noted that many composite cements are promoted by manufacturers as universal, but this term is nothing more than a marketing gimmick. When purchasing such material, you must carefully study the instructions to understand what the manufacturer actually meant by the word “universal.”

Light-curing composite cements used in combination with the total etch technique

Cements of this group are used in combination with the total etching technique, that is, the tooth must be etched, the acid washed off, and a bonding agent applied before fixing the crown.

These cements come in a variety of colors and are usually sold as a system of two syringes, one containing the base and the other containing the catalyst. The base can be used without a catalyst, in which case it is necessary to expose the restoration to light to harden the cement. When the base and catalyst are mixed together, a dual-cure cement is obtained. Composite cements of this group should be used only when the cement can be exposed to light of sufficient intensity. A typical indication for this cement is the cementation of veneers on anterior teeth made of transparent glass ceramics (eg lithium disilicate).

Dual-cure composite cements used in combination with the total etch technique

Cements of this group are produced in a double syringe. When squeezed out of such a syringe, the base and catalyst are mixed. Cements of this group are also available in various colors and are produced by many manufacturers. An example of a cement in this group in this article is Calibra Ceram cement (Dentsply Sirona) (Fig. 2-8). Composite cements of this group are also used in the total etching technique, which requires etching the tooth, washing off the acid and applying an adhesive.

Dual-cure CCs used in combination with the total-etch technique are excellent for cases where the tooth core will not support the retention of the restoration, as well as in areas of the mouth where the use of light for curing is difficult.

Self-etching composite cements

A recently developed category of cements is self-etching CC (Fig. 9-13). These cements include an etching and bonding system. Therefore, they are also called self-adhesive cements. The distinctive basis of cement is the special primer included in it, which penetrates through the smear layer of the tooth. These dual-cure cements and excess cement are easily removed after pre-curing the crown margin for 5-10 seconds. Self-etching cements are a good choice in situations where tooth cores contribute to the retention of the restoration, as well as in some cases where retention geometry is insufficient and can be used with all-ceramic lithium zirconium disilicate crowns.

Rice. 9. Prepared tooth stump with good retention properties. The crown is ready to be cemented using Calibra Universal dual-curing self-etching cement (Dentsply Sirona).

Rice. 10. Primer Z-PRIME Plus (BISCO Dental Products) applied to a zirconia crown (BruxZir)

Rice. 11. The crown is filled with self-etching composite cement Calibra Universal

Rice. 12. The crown, fixed after adding cement, was preliminarily illuminated from the side of the tongue for 3 seconds

Rice. 13. Pay attention to the ease of removing excess after preliminary highlighting

In general, the clinician may consider the total etch technique in the following situations:

- After preparation, dentin is almost absent

- The tooth can be qualitatively isolated to create a dry field and carry out bonding

- The geometry of the stump creates conditions for holding the restoration

Self-etching systems can be used:

- Little enamel

- Core geometry promotes retention

If there are small islands of enamel on the stump, it is necessary to carry out a short 3-5 second etching with orthophosphoric acid and subsequently use self-etching composite cements. It is also important to remember that under-etching and over-etching can reduce adhesion strength, so there needs to be a balance in the process.

Conclusion

In the last decade, certain advances have been made in materials science for indirect restorations, which has made it possible to produce higher-quality restorations with a longer service life.

With so many different cements available, it is necessary to understand how to prepare a tooth and how preparation design influences the choice of cement.

What should determine our actions is the clinical situation and the ability of the tooth core to retain the restoration.

Gone are the days when the dentist had at his disposal only one universal cement for all occasions. Now experienced doctors have several different cements at hand and have a clear idea in what clinical situations they can be used.

about the author

Dr. Simos is in private practice in Bolingbrook, Illinois, USA. He received his degree from Loyola University Chicago and is the founder and president of Allstar Smiles Training Center in Bolingbrook, where he teaches postgraduate courses to practicing dentists on the topics of cosmetic dentistry, occlusion and restorative dentistry.

The translation was made by Olga Yukhimenko specifically for the StomPort.ru portal.

Clinical case

It was decided to replace the old metal-ceramic crown of tooth 25 with a restoration made of IPS E.max press – a partially filled glass-ceramic based on lithium disilicate.

The restoration can be cemented using MSIC, self-adhesive or adhesive composite cement. I prefer to cement lithium disilicate restorations using adhesive cements as opposed to zirconium oxide restorations. This is due to the lower strength of these restorations.

The restoration was etched with 5% hydrofluoric acid for 20 seconds as this was not done in the laboratory. Then the inner surface of the restoration was treated with alcohol. Ceramic bond from Voco was applied, exposure 60 seconds. Before applying the cement, the bond was inflated with a blower for uniformity (Fig. 1).

The tooth was anesthetized to reduce sensitivity during the cementation process. After the onset of anesthesia, the tooth stump was treated with 2% chlorhexidine from Ultradent (Fig. 2). This step is optional, but chlorhexidine is a good antiseptic and does not reduce bond strength. Futurabond U from Voco was then applied for 20 seconds and gently inflated for 5 seconds (Figure 3).

Once the restoration and tooth were prepared, Voco's Bifix QM cement was applied and the restoration was carefully secured to the tooth under slight pressure (Figure 4). After installation, the restoration was illuminated for 2 seconds (Fig. 5). Excess cement can be easily removed using a float (Fig. 6), and the restoration is finally polished (Fig. 7-8).