Do you want to have healthy teeth and a beautiful smile? Monitor the condition of your gums. Soft tissues perform many important functions, so they must be protected. Proper nutrition, careful grooming and regular dental checkups significantly reduce the risk of developing gum disease.

However, gingivitis, periodontitis and other diseases are not the only causes of gum inflammation. This disorder can also be a consequence of a tooth bruise. Let's look at what leads to injuries and what complications can arise.

Dental periodontitis - what is it?

Periodontium refers to the whole complex of tissues responsible for tooth retention: connective fibers, blood vessels, periodontium, gums, canals and jaw bone. Periodontitis is an inflammation of the gum tissue, which quickly affects the rest of the complex. As a result, the dentogingival connection is disrupted and the tooth falls out. Periodontitis is a very common disease that affects more than 95% of the world's inhabitants in various stages: from the rudimentary form of periodontitis to advanced, untreatable.

It is believed that most often the pathology manifests itself in men and women aged 30 to 40 years and in adolescents 16-18 years old. However, the disease can affect anyone, regardless of gender and age, if you do not monitor the condition of your oral cavity and postpone a visit to the dentist. Periodontitis can be treated only in the early stages; when it becomes chronic, no dentist, even the most modern, can cope with it, since the tissues have undergone irreversible changes.

Mechanical damage to the gums: how to treat

Damage to the gums is a serious problem, which in some cases requires the intervention of a specialist. It is better not to self-treat gum damage. But you can familiarize yourself with general recommendations on how to behave immediately after an injury:

- Use an antiseptic solution and rinse your mouth twice a day

- Take painkillers

- Eat on the other side so as not to provoke an attack of pain

- If possible, consult a dentist as soon as possible to avoid suppuration and other complications.

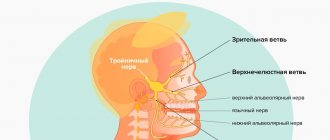

Etiology of periodontitis

Periodontitis can be caused by various factors.

- Microbes.

The oral cavity of any person is inhabited by pathogenic microorganisms that do not cause harm if proper nutrition and hygiene are observed. But, if the patient constantly consumes carbohydrates and neglects to use dental floss, bacteria actively develop and gradually affect the enamel, dentin and reach the periodontal tissues. - Genetic predisposition.

If for many generations all family members have suffered from this disease, there is a high probability of adopting this predisposition. Heredity plays a big role in the development of gum periodontitis, even if a person carefully monitors hygiene and eats right. - Mechanical damage to the gums.

Tissue bruise due to negligence, an incorrect bite, in which increased pressure is applied to a specific area of the gum, or an oversized filling, due to which the tooth puts increased pressure on the gum and damages it. - Systemic diseases.

Dental diseases and periodontitis can cause pathologies not related to the oral cavity, such as vegetative-vascular dystonia, HIV, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and gastrointestinal diseases. - Autoimmune diseases.

Reduced immunity, disruption of the endocrine system, hormonal imbalances during pregnancy. - Poor quality dentist work.

Tissue damage during treatment, an unsuitable crown, incorrectly installed braces and other tissue injuries due to the fault of the doctor can provoke periodontitis.

Among the given factors are microbial causes of the development of periodontitis, and microbes are known to be transmitted from one person to another. So is periodontitis contagious? No, directly, for example, by airborne droplets or through saliva, it is impossible to become infected with the pathology, and every person has microbes that provoke the disease - even if periodontitis bacteria are transmitted from a sick person to a healthy person, the microbes will not develop without additional favorable circumstances: poor oral hygiene, gum injuries, predisposition or concomitant diseases.

How to treat mechanical gum damage

To help the patient, the doctor will first eliminate the causes of inflammation:

- if necessary, remove the foreign body

- will replace low quality fillings

- will consider alternative options to replace uncomfortable dentures

- recommend a new toothbrush

If the gums are damaged by a toothbrush, the accessory must be replaced, choosing it according to the degree of stiffness of the bristles. Your doctor will help you make your choice. Below we will consider how doctors suggest treating mechanical damage to the gums:

- Treatment and procedures for pain relief of the damaged area. Applications with lidocaine solution help. Some dentists recommend propolis preparations to patients for these purposes.

- Treatment of inflammation. To prevent infection, the drugs Chlorhexidine, Miramistin or furatsilin will be prescribed. You can also use traditional medicine: decoctions of chamomile and sage. Gels against gum inflammation show a good effect: Metrogyl Denta, Cholisal.

- Healing procedures. Gels, ointments and balms containing vitamin A and E work well.

If the size of the damage is small, then sutures are not required. It is better to check with a professional about treating gum damage rather than trying to prescribe medications on your own.

Symptoms of periodontitis in adults and children

Typically, the signs of periodontitis vary depending on the stage of development of the disease, but there are also general symptoms characteristic of the entire period of pathology:

- unpleasant constant bad breath, plaque and tartar are associated with the active activity of bacteria;

- bleeding and brighter gum color due to tissue inflammation;

- increased sensitivity of teeth, pain when chewing;

- thick viscous saliva;

- swollen lymph nodes;

- headache, weakness and lethargy.

Stages of periodontitis

With each stage, dental periodontitis develops more strongly. Unfortunately, most often patients consult a doctor already with a severe form of the disease.

Mild periodontitis

There is bleeding of the gums when brushing teeth, small periodontal pockets up to 3 mm deep, slight swelling of the gums and discoloration - the tissues look loose and slightly blue. The initial stage is almost painless and can be treated in just a couple of visits to the dentist.

Moderate periodontitis

The gums bleed almost constantly, and small purulent discharge appears. Gum pockets enlarge and expose the roots of the teeth, and the interdental spaces widen. The patient feels the tooth bursting and increased pressure on the gum tissue. It is difficult to cure moderate periodontitis, but it is quite possible if you make an effort and follow the doctor’s instructions.

Severe periodontitis

The gums are completely weakened, the tissues are loose, there is no swelling. Severe tooth mobility and even tooth loss. Bone tissue with severe periodontitis becomes thinner and atrophies. The entire complex is affected - ligaments, muscles, periodontal tissues and blood vessels, and nutrition of the tooth stops. The only thing a specialist can do at this stage is to relieve gum inflammation and recommend tooth extraction for prosthetics.

When is a visit to the dentist necessary?

It is advisable to seek help immediately as soon as the following symptoms appear:

- General health has deteriorated significantly

- subfebrile body temperature is within the range of 37.2? C - 37.5? C

- a slight increase in the level of leukocytes in the CBC was noted

- formations (seals) detected

With a weakened immune system, the injured area can take quite a long time to heal. If, after examination, the dentist determines that the gums (or teeth) are damaged as a result of the impact of the denture, the patient will be referred to an orthopedist.

Forms of periodontitis

Types of periodontitis are classified into groups according to different criteria.

By place of development:

- localized - a small lesion affecting only one tooth, and sometimes part of the tooth, for example the root; most often occurs due to mechanical damage to tissue;

- generalized - the damage spreads to a group of teeth, gum and bone tissue, so it seems that half of the jaw hurts; A common cause is the development of bacteria and reduced immunity.

According to the nature of the course:

- acute - pain during periodontitis occurs suddenly, symptoms develop rapidly;

- chronic - advanced periodontitis of the acute stage becomes chronic, pain and other symptoms practically disappear, but the disease continues to progress and destroy tissue.

Preventive measures

It is rare to avoid gum injury under certain circumstances, but there are some preventive measures you should know:

- Try to eat carefully. Without being distracted by conversations or watching movies. This will minimize the likelihood of mechanical injury or burns.

- Teeth should be treated on time. Immediately after the onset of painful sensations, you should consult a dentist.

- Prosthetic procedures take place in reliable and certified clinics.

- Do not self-medicate under any circumstances; do not take antibiotics or other serious medications without a doctor’s prescription.

- Try to brush your teeth properly. If necessary, use a soft-bristled brush.

Exacerbation of periodontitis

The disease does not occur in isolation; periodontitis affects the condition of the entire organism. Even if the pathology has passed from an acute form to a chronic one and it seems to the patient that the pain has gone away and the illness has receded, the destructive effect of the inflammatory process still continues. And the advanced chronic stage can not only worsen, but also cause severe complications of periodontitis:

- osteomyelitis - inflammation of bone tissue;

- abscess and phlegmon - the formation of abscesses and the spread of pus through the tissues;

- lung diseases - pathogenic bacteria from the oral cavity enter the lungs when breathing;

- pathologies of the heart and blood vessels - a long-term inflammatory process affects the functioning of the heart.

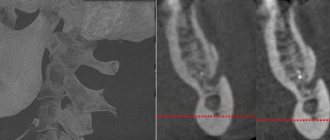

Diagnosis of periodontitis

Diagnostics includes a visual examination to determine the presence of problems and analysis of complaints to make a preliminary diagnosis. Then the patient is sent for additional examination:

- orthopantomogram - a circular image of the entire jaw;

- X-ray - X-ray of periodontitis on a specific tooth using a targeted image;

- periodontogram - measuring the depth of periodontal pockets;

- urine and blood analysis - determination of infections and diseases in the body.

The symptoms of the disease are similar to those of other dental pathologies; the doctor’s task is to make an accurate diagnosis for effective treatment.

- With periodontal disease, there is no bleeding, swelling of the gums and periodontal pockets, there is no inflammation, since the main cause is age-related changes, diabetes mellitus and cardiac dysfunction. Read more about periodontal disease in a separate article.

- With gingivitis, periodontal pockets and tooth mobility are not observed, there is no exposure of the roots, and inflammation affects only the gum tissue. Find out about the symptoms of the disease here.

- Stomatitis is accompanied by plaque on the tongue and ulcers on the mucous membrane, bleeding and inflammation of the gums, tooth mobility and exposure of the roots are absent. About the types and signs of the disease in a separate article.

Traumatic lesions of the oral mucosa

- Chronic mechanical injury

Clinical manifestations of a traumatic ulcer depend on the strength of the damaging factor, the general reactivity of the body, the state of the microbiocenosis of the oral cavity and other factors. As a rule, a traumatic ulcer is single. The mucous membrane around the ulcer is hyperemic and swollen. A traumatic ulcer is always painful, has uneven edges, and its bottom is covered with a fibrinous coating that can be easily removed. With the long-term existence of an ulcer, its edges and base become denser (due to the predominance of the phenomenon of proliferation). The edges of the ulcer are hyperemic, painful on palpation, the bottom is often bumpy, covered with necrotic plaque. The depth of the ulcer varies down to the muscle layer. Regional lymph nodes are enlarged, mobile, and painful on palpation.

Traumatic ulcers can be complicated by fusospirochetosis or candidiasis, and with a long course (2-3 months) they can become malignant.

- A traumatic ulcer must be differentiated from:

- ulceration of a cancerous tumor,

- tuberculous ulcer,

- syphilitic chancre,

- chronic ulcerative necrotic gingivostomatitis Vincent,

- trophic ulcer.

Removal of the traumatic factor also serves differential diagnostic purposes. Rapid healing of the ulcer within a few days indicates its traumatic origin.

The bone tissue of the alveolar process is resorbed in places, the alveolar edge becomes soft, mobile (“dangling”). Angular cheilitis often develops simultaneously. In the occurrence of such conditions, in addition to chronic trauma, a certain role is played by the influence of fungi of the genus Candida, which, as a rule, are found in large quantities on prostheses, and less on the mucous membrane of the prosthetic bed. You should also remember about the possibility of an allergic reaction of the oral mucosa to the base material of the prosthesis (usually acrylic plastic).

- Chemical damage

In case of acute injury, sharp pain usually occurs immediately and is localized at the site of contact with the chemical. The clinical picture depends on the nature and amount of the damaging substance and the time of action.

Burns with acids lead to the appearance of coagulative necrosis on the mucous membrane - a dense film of brown (from sulfuric acid), yellow (from nitric acid) or white-gray (from other acids) color. The films are tightly fused to the underlying tissues and are located against a background of pronounced inflammation of the mucous membrane with swelling and hyperemia.

A burn with bases (alkalies) causes liquefaction necrosis of the mucous membrane, while a dense film is not formed, necrotic tissue has a jelly-like consistency. The damage is deeper than with an acid burn. Necrosis from alkali burns can involve all layers of soft tissue, especially on the gums and hard palate. Burns, especially extensive ones, cause severe suffering to the patient. A few days after the necrotic tissue is sloughed off, slowly healing erosive or ulcerative surfaces are exposed. In mild cases, alkali burns can only cause a catarrhal inflammatory process.

Symptoms of “galvanism” should be differentiated from stomalgia, glossalgia, and allergic stomatitis.

Anamnesis (absence of symptoms of “galvanism” before prosthetics), as well as measurement of the magnitude of microcurrents in the oral cavity, are important in the differential diagnosis.

- Radiation sickness

Radiation sickness (morbus radialis) develops as a result of exposure to ionizing radiation on the entire body or its large parts: chest, abdomen, pelvic area.

Radiation damage can be caused by any type of ionizing radiation: X-rays, beams, neutron fluxes, etc. In irradiated tissues, the morphological structure of the walls of blood vessels changes, the barrier function of connective tissue decreases, and regeneration is suppressed. There are acute and chronic forms of radiation sickness.

Acute radiation sickness (morbus gadialis acutus) develops after a single irradiation of the body with massive doses (1 - 10 Gy, or 100 - 1000 rad). In the first period - the period of primary reactions, which begins soon after irradiation (1-2 hours) and lasts up to 2 days, dryness (or salivation) appears in the oral cavity, taste and sensitivity of the mucous membrane decrease. The mucous membrane of the mouth and lips swells, hyperemia appears, and pinpoint hemorrhages may occur. In the second, latent period, which lasts from several hours to 2 weeks, all these phenomena disappear. The period of pronounced clinical phenomena (third period) is the height of the disease. Against the background of a sharp deterioration in the general condition, changes in the oral cavity reach a maximum. A burning sensation appears, the mucous membrane becomes anemic and dry. A picture of radiation stomatitis appears.

Changes in blood vessels and blood composition during this period cause the phenomena of hemorrhagic diathesis: increased bleeding, multiple petechial hemorrhages. Due to a sharp decrease in tissue resistance, a rapidly developing autoinfection, especially putrefactive one, occurs.

Thus, the clinical picture of radiation stomatitis consists mainly of hemorrhagic syndrome and necrotic ulcerative process. The latter is most pronounced in places of injury with overhanging fillings, sharp edges of teeth, dentures, tartar, and where there were accumulations of microflora before the disease, i.e. First, the edge of the gums and tonsils are affected, and then the lateral surfaces of the tongue and the palate. In areas adjacent to the mucous membrane of metal prostheses and fillings, the damage may be more pronounced due to secondary radiation. The mucous membrane of the mouth, lips and face swell. The gingival papillae loosen, bleed, and then the gum edge becomes necrotic. The bone tissue of the alveolar process is resorbed, the teeth become loose and fall out. Multiple necrosis of the mucous membrane does not have sharp boundaries, the inflammatory reaction of surrounding tissues is mild. The bottom of the ulcers is covered with a dirty gray necrotic coating with a putrefactive odor. In severe cases, necrosis can spread from the mucous membrane to the underlying soft tissue and bone, radiation necrosis of the bone occurs with sequestration, and jaw fractures are possible. This is facilitated by the spread of infection from foci of chronic periodontitis and periodontitis.

The tongue swells, becomes covered with a thick coating, cracks, hemorrhages and necrosis appear, most often in the area of the root of the tongue; taste and sensitivity disappear. Severe necrotizing tonsillitis develops. If the patient does not die, then the fourth period begins - recovery: a slow reverse development of the symptoms of the disease occurs. In the oral cavity, everything also returns to relative normal. During this period, relapses of the disease are possible.

Chronic radiation sickness (morbus radialis chronicum) develops as a result of prolonged exposure to low doses of radiation on the entire body or a significant part of it. The oral cavity is sensitive to the effects of ionizing radiation, so at the onset of the disease, changes in the oral cavity can be especially pronounced. Dryness gradually increases due to damage to the salivary glands. Persistent catarrhal gingivitis occurs, which can subsequently develop into ulcerative gingivitis. Initially, erosions and ulcers may appear along the transitional folds on the vestibular side, followed by damage to the gums and red border of the lips.

Glossalgia may develop, and then glossitis with swelling of the tongue, cracks, and coating on the tongue. The long course of chronic radiation sickness usually leads to a picture similar to periodontitis - the so-called radiation periodontitis.

The reaction of the mucous membrane to radiation develops gradually - from hyperemia and swelling to the appearance of erosion. This reaction has its own characteristics in different areas of the mucous membrane. The first clinical signs on the mucous membrane, which does not have a keratinized layer in the epithelium (cheeks, floor of the mouth, soft palate), are manifested by mild hyperemia and swelling, which increase as the absorbed dose increases. Then the mucous membrane becomes cloudy, loses its shine, thickens, wrinkles appear, and when scraped, the surface layer is not removed. This occurs due to increased keratinization of the epithelium. Some affected areas resemble leukoplakia or lichen planus. If the radiation dose increases, the keratinized epithelium in some areas is rejected, desquamated, erosions appear, covered with a sticky necrotic plaque - focal membranous radiomucositis develops. Then the epithelium is rejected over large areas, the erosions merge and focal radiomucositis transforms into confluent membranous radiomucositis. The mucous membrane of the soft palate is highly radiosensitive, there is no keratinization stage when it is irradiated, and the reaction develops faster than in other parts of the oral cavity. In areas of the mucous membrane that are normally subject to keratinization, the radiation reaction proceeds more favorably and leads only to focal desquamation of the epithelium or single erosions.

The course of pathological processes in the oral mucosa is complicated by damage to the salivary glands (with remote irradiation methods). At the beginning (the first 3-5 days), increased salivation may be observed, which is quickly replaced by dry mouth up to complete xerostomia, which is practically impossible to stimulate.

The consequence of the death of the taste buds of the tongue is a violation of taste. At first, sensations in the tongue may manifest themselves as glossalgia, then a perversion of taste is noted, and later - loss of it.

Radiation changes in the oral cavity are largely reversible. After cessation of irradiation or during a break in treatment, the mucous membrane quickly returns to relative normal. This period lasts 2-3 weeks. With a large absorbed dose (more than 50-60 Gy, or 5000-6000 rad), irreversible changes in the salivary glands and mucous membrane (edema, hyperemia, telangiectasia, atrophy, radiation ulcers) may occur.

Radiation therapy should be preceded by sanitation of the oral cavity, since the reaction of the mucous membrane to radiation exposure is more severe in an unsanitized oral cavity.

Due to trophic disorders, the reactivity of the mucous membrane to mechanical trauma and infection is sharply reduced. The edematous mucous membrane with defective epithelial cover is easily injured by the sharp edges of teeth and dentures, which can lead to the appearance of sharply painful, long-term non-healing ulcers.

- Leukoplakia

The initial manifestations of leukoplakia are usually invisible, since there are no subjective sensations. Leukoplakia begins with the appearance of areas of clouding of the epithelium (grayish in color, with elements of keratinization on the surface). The lesion occurs against the background of an unchanged mucous membrane. Typical localization of the focus of leukoplakia is the mucous membrane of the cheeks along the line of closure of the teeth in the anterior section, the corners of the mouth and the red border of the lower lip without skin lesions. The dorsum and lateral surfaces of the tongue are somewhat less commonly affected. Smokers are characterized by lesions of the palate, described as “Tappeiner smokers' leukoplakia.”

There are the following forms of leukoplakia: flat or simple, verrucous and erosive. These forms can transform one into another. It is possible to combine different forms of leukoplakia in different areas of the oral mucosa in the same patient. The disease begins with the appearance of a flat shape.

Flat, or simple, leukoplakia (leukoplakia plana) is the most common. This form usually does not cause subjective sensations and is discovered by chance. Sometimes patients have complaints of a feeling of tightness, burning, and an unusual appearance of the mucous membrane. In the presence of extensive lesions on the tongue, taste sensitivity may be reduced. The main morphological element of the lesion in flat leukoplakia is a hyperkeratotic spot, which is an area of turbidity of the epithelium with clear contours. During the examination, foci of hyperkeratosis of various shapes and sizes are revealed, not rising above the level of the mucous membrane, but with clear boundaries of the lesion. Elements of flat leukoplakia resemble a burn of the mucous membrane with lapis, thin tissue paper pasted on, or a white coating that does not come off even with intense scraping. The keratinization can vary in intensity, so the color of the affected areas varies from pale grayish to intensely white.

The surface of the area of flat leukoplakia is usually slightly rough and dry. There is no compaction at the base of the lesion, just as there is no visible inflammatory reaction along its periphery.

There is a direct connection between the shape, color, size of keratinized areas and their location. Thus, with hyperkeratosis of the mucous membrane in the area of the corners of the mouth, symmetry of the lesion is observed in 85% of cases. The shape of the lesion has the shape of a triangle, the base of which faces the corner of the mouth, and the apex faces the retromolar space.

When the focus of leukoplakia is localized on the mucous membrane of the cheeks along the line of closure of the teeth, the elements of the lesion represent an elongated line, the continuity of which may be disrupted in certain areas. Leukoplakia on the red border of the lips looks like sticky tissue paper of irregular shape and grayish-white color (Fig. 11.5). Limited areas of lesions form on the mucous membrane of the tongue, hard palate, and floor of the mouth, sometimes resembling wide stripes or solid spots. More extensive lesions are also noted.

The relief of the mucous membrane and its turgor are also reflected in the appearance of the lesion. So, if leukoplakia develops against the background of folding of the tongue, the protruding areas become more keratinized and the surface of the tongue resembles a cobblestone street. A similar picture can be seen with a decrease in turgor and folding on the cheeks. If there is no pronounced folding on the tongue, flat leukoplakia looks like grayish-white, slightly sunken spots, the papillae of the tongue on them are smoothed.

Tappeiner's leukoplakia (leucoplakia nicotinica Tappeiner, nicotinic leukokeratosis of the palate) occurs in heavy smokers (especially pipe smokers). The mucous membrane of the hard palate and the adjacent part of the soft palate is mainly affected. Sometimes the gum margin is involved. The mucous membrane in the affected area is grayish-white in color, often folded. Against this background, mainly in the posterior half of the hard palate, red dots stand out - the gaping mouths of the excretory ducts of cystically dilated salivary glands, looking like small nodules. They are formed due to blockage of the excretory ducts by hyperkeratotic masses. Damage to the palate in smoker's leukoplakia can be combined with the location of elements on the mucous membrane of the cheeks, corners of the mouth, lower lip, etc. This form of leukoplakia is an easily reversible process: stopping smoking (an irritating factor) leads to the disappearance of the disease.

Verrucous leukoplakia (leucoplakia verrucosa) is the next stage in the development of flat leukoplakia. This is facilitated by local irritants: trauma with sharp edges of teeth and dentures, biting areas of leukoplakia, smoking, eating hot and spicy foods, microcurrents, etc.

The main feature that distinguishes this form of leukoplakia from flat one is more pronounced keratinization, in which a significant thickening of the stratum corneum is detected. The area of leukoplakia rises significantly above the level of the mucous membrane and differs sharply in color. Upon palpation, a superficial compaction may be detected. Patients usually complain of a feeling of roughness and tightness of the mucous membrane, burning and pain when eating, especially spicy food.

There are plaque and warty forms of verrucous leukoplakia. In the plaque form, limited milky white, sometimes straw-yellowish plaques with clear contours are identified, rising above the surrounding mucous membrane. The warty variety of verrucous leukoplakia is characterized by dense grayish-white bumpy or warty formations, rising 2-3 mm above the level of the mucous membrane. The warty form of leukoplakia has a greater potential for malignancy compared to the plaque form. On palpation, the lesions are dense, painless, and not fused with the underlying areas of the mucous membrane. The thickness of the raised areas of hyperkeratosis varies from pronounced to barely noticeable during normal examination. With a slight elevation of the elements, the affected area is almost not determined by palpation. A leukoplakic lesion of considerable thickness becomes dense to the touch, and it is not possible to fold it.

Erosive leukoplakia (leukoplakia erosiva) is actually a complication of simple or verrucous leukoplakia due to trauma. With this form of leukoplakia, patients complain of pain, which intensifies under the influence of all types of stimuli (eating, talking, etc.). Usually, against the background of foci of simple or verrucous leukoplakia, erosions, cracks, and, less often, ulcers occur. Erosions are difficult to epithelialize and often recur. Patients are especially concerned about erosion in the keratinized area of the red border of the lips. Under the influence of insolation and other irritating factors, they increase in size without showing a tendency to heal. The pain intensifies.

Pathohistologically, thickening of the epithelium is revealed due to the proliferation of the horny and granular layers. The stratum corneum reaches considerable thickness, especially with the verrucous form of leukoplakia. In it, foci of hyperkeratosis often alternate with foci of parakeratosis. The granular layer of epithelium in the affected area has varying degrees of severity. Verrucous and erosive forms of leukoplakia are characterized by pronounced hyperkeratosis and acanthosis. Acanthosis in leukoplakia can be significant if the keratinization has the character of parakeratosis; conversely, with severe hyperkeratosis, acanthosis is minimal or completely absent. In the connective tissue stroma of the affected areas of the mucous membrane, diffuse chronic inflammation is determined with pronounced infiltration of the surface layers by lymphocytes and plasma cells, the manifestation of sclerosis. The latter explains poor healing and frequent relapses with the appearance of cracks and erosions, which is most typical for the plaque form of leukoplakia.

Leukoplakia is a precancerous condition, since all its forms can become malignant with varying degrees of probability, transforming into spinocellular cancer.

Flat leukoplakia malignizes in 3-5% of patients, and in some the process of malignancy occurs quickly (1-1.5 years), in others the disease can exist for decades without transforming into cancer. Most often, malignancy occurs in verrucous and erosive forms of leukoplakia (in 20% of cases).

Clinical signs of malignancy are increased keratinization processes; rapid increase in the size and density of the lesion; the appearance of compaction at the base of the plaque, erosion; papillary growths on the surface of erosions, bleeding due to injury; the appearance of non-healing cracks.

- Soft leukoplakia Pashkova

Characterized by the presence of areas of peeling, slightly swollen, pasty mucous membrane with unclear boundaries, without inflammation or compaction. The mucous membrane has a grayish-white color. Most often, soft leukoplakia is localized on the mucous membrane of the cheeks along the line of closure of the teeth and lips, and less often on the tongue and gums. The lesion can be limited or diffuse, when almost the entire mucous membrane, and sometimes the red border of the lips, is involved in the process. In patients with neuropathy, predominantly young, with habitual biting or sucking of the cheeks, lips, tongue, the epithelium along the line of closure of the teeth is unevenly desquamated, has a fringed appearance due to the presence of multiple small flaps, which causes the unevenness of the affected surface (it looks like it is moth-eaten). This altered epithelium is partially removed by scraping. In severe cases, painful erosions may occur from biting the epithelium.

Histologically, pronounced parakeratosis and acanthosis are noted. At all levels of the spinous layer there are so-called “light” vacuolated cells, the cytoplasm of which is almost not stained, and the nuclei are deformed (pyknotized). In the connective tissue layer, expansion of small blood vessels, thickening of collagen, and thinning of elastic fibers are detected.

- White spongy nevus of Cannon

White spongy nevus may appear in early childhood or later, then progresses and reaches its maximum development during puberty. The disease may then regress or remain unchanged.

There are no subjective sensations. Patients may complain of an unusual appearance of the mucous membrane.

The typical location of a white spongy nevus is the buccal mucosa. The lesion is always symmetrical. The mucous membrane of the cheeks is white or grayish-white, somewhat thickened, soft, as if spongy, strongly folded. In some cases, the folding and wrinkling of the mucous membrane is so pronounced that the folds hang into the oral cavity. The surface layers of the epithelium are removed by scraping. At the same time, similar lesions may appear on the mucous membrane of the genital organs and rectum.

White spongy nevus should be differentiated from:

- flat leukoplakia;

- candidiasis;

- lichen planus;

- soft leukoplakia.

There is great clinical similarity between white spongy nevus and soft leukoplakia. Some authors consider white spongy nevus and soft leukoplakia to be different clinical forms of the same disease related to nevi, but there are quite pronounced differences between them. White spongy nevus, unlike soft leukoplakia, occurs mainly in childhood and is often hereditary. The development of mild leukoplakia, as a rule, is associated with various kinds of neurotic reactions or with hormonal changes in the body (puberty, postmenopause).

Patients with Cannon's nevus have congenital defects in the structure and maturation of the epithelium of the oral cavity, and in some cases, the genitals and rectum. With mild leukoplakia, the oral mucosa initially has a normal appearance, and its pathological changes are associated with the action of irritating factors against the background of neurological disorders or hormonal dysfunctions. In addition, damage to the oral mucosa with white spongy nevus is usually generalized.

Treatment of periodontitis

Treatment of periodontitis in the early stages consists of removing plaque and tartar, cleaning periodontal pockets and drug therapy: local treatment of tissues with anti-inflammatory drugs, taking antibiotics and strengthening the immune system.

Moderate to severe disease requires complex therapy for periodontitis. In addition to sanitation of the oral cavity and taking medications, it includes splinting teeth to keep them from moving, surgery to remove pus and affected tissue, consultation with a therapist, immunologist and gastroenterologist to prevent relapse; in the case of an advanced form of the disease - examination by a prosthetist and subsequent restoration of lost teeth using crowns. Read more about the treatment of periodontitis in our article.

Dentists always aim to preserve the patient’s natural teeth, but in cases of severe periodontitis, often the only solution is tooth extraction. You shouldn’t let your oral cavity reach this state; seeing a doctor at the first symptoms of the disease gives you a 100% chance of recovery—the early stages of periodontitis can be treated quickly and without complications. And regular visits for preventive examinations completely exclude the occurrence of any dental diseases.